Graduation

It’s amazing how quickly time goes by. Three years and seven semesters later, my time in Blacksburg has come to an end. Graduation took place last Thursday on May 9th, and now with my thesis (Electronic Thesis Dissertation) successfully submitted and approved by the graduate school, I can proudly declare that I have officially earned my Masters of Architecture from Virginia Tech.

It has been a fantastic journey. I am extremely proud of myself for following through with it and I wouldn’t change anything if I could. Of course, there were times when I wondered what it would have been like to attend a different school and how it would have shaped me. But, to change the past would be to change the experiences that shaped me and molded me into the architect that I aspire to be.

At Virginia Tech, I cultivated my love for architecture in a way that I never thought possible. I eagerly absorbed every lecture, constantly fueled by curiosity and driven to ask questions. I found my affinity for adaptive reuse inspiring my thesis project. I have come to understand the architect that I would like to become: one committed to effecting positive change in the lives of others. Architecture does not exist in isolation, but as a reflection of the people it serves. If we aren’t building for the people who will inhabit these spaces, then who are we building for?

During my time at Virginia Tech, I’ve had the opportunity to make some great friends and meet a lot of fantastic people. Yet, the bittersweet reality is that now we are all embarking on our separate paths, uncertain when we’ll meet again. Despite our diverse backgrounds and different life experiences prior to graduate school, we cultivated a bond through our shared experience over the last three years.

As my friends disperse to places such as Seattle, Richmond, Philadelphia and elsewhere, my own destination is less certain. My plan is fluid and I’m open to whatever may come. I may try to move to Australia. After S. Korea I had plans to do a working holiday visa, but when Covid happened, I changed my plans and I decided to pursue graduate school. It was fortuitous because otherwise I’m not sure that I would have made the decision. Australia has numerous visa opportunities and architect is one under their skilled labor shortage, so it’s a possibility.

If that doesn’t work out, I may try California. I’ve always wanted to try living on the west coast. My sister lives out there now, and was looking for graduate programs, but the costs were above anything I could afford. One year at the University of Southern California, was estimated to cost around $75,000, not much more than my three years at Virginia Tech. So, who knows?

Tonight, I’m embarking on a six-week architectural journey, visiting friends and seeing monuments across Europe and Egypt and when I return, I’ll focus on the future.

My Apartment

I’m going to miss living in Blacksburg, it’s a beautiful area nestled within the Blue Ridge Mountains. Among the many things I’ll miss, my apartment holds a special place in my heart. I lived in the same apartment for the last three years. It was perfectly located, only a 15-minute walk from the architecture building and conveniently located near downtown and dominos.

The complex was quiet and I lived on the third floor with nobody above me. I only had one neighbor to my left. While my view was of the parking lot, it was filled with trees and the backdrop of the mountains adding to the ambiance. Natural light flooded through my windows, illuminating my two living spaces. My friend joked that during our zoom class she could tell that the sun was out based on my screen.

My walls were adorned with the artwork I collected over the years, the first time they have been in a single space. I also cultivated a thriving plant collection (thanks to the natural light) and propagated numerous ones. Whenever I opened my door, serenity washed over me. I loved that space. I bought most of the furniture new because I figured I’d take it with me wherever I ended up after, but since I don’t know where I’m going, or if it’s even going to be in this country, I had to part with almost all of it. Selling the furniture and plants was like selling pieces of me. My apartment transformed into a shell of its former self.

Thesis

Thesis was intense. It consumed my every waking moment. If I wasn’t working on it, I was thinking about what needed to be done. Describing it is challenging because there’s no end goal or finish line to cross that signals completion. Technically you may never be done because there is always more to explore and produce, so it makes it extremely difficult to gauge progress.

At the beginning of the year, we choose three committee members. One as the chair and shoulders the main burden for meetings and approvals and two more as members. The three of them become both advisers and critics as the year went on. Throughout the year, I’d have to set up meetings, together or individually to discuss my project, show my progress and to get advice on how to move forward. There were other professors as well who played a pivotal role in my journey. But, when the second semester came intofocus,s too many opinions saying different things limited my desire to reach out to others.

The most difficult thing about thesis is the lack of a clear direction. There is nobody telling you what you have to do or what you need and there is no correct path to follow. Unless my friends were in architecture, I hardly saw them from Spring Break in early March until my thesis defense on April 30th. It was even harder to maintain a relationship with my girlfriend because it was difficult to find the time to get together. I was in studio during the week until 8 or 9 at night, sometimes later and on the weekends. If I wasn’t in studio I was working at home. In addition to working on thesis, I had a 20-hour a week graduate assistantship and three other classes that I had to focus on. To say I was stretched thin, is an understatement, but I survived.

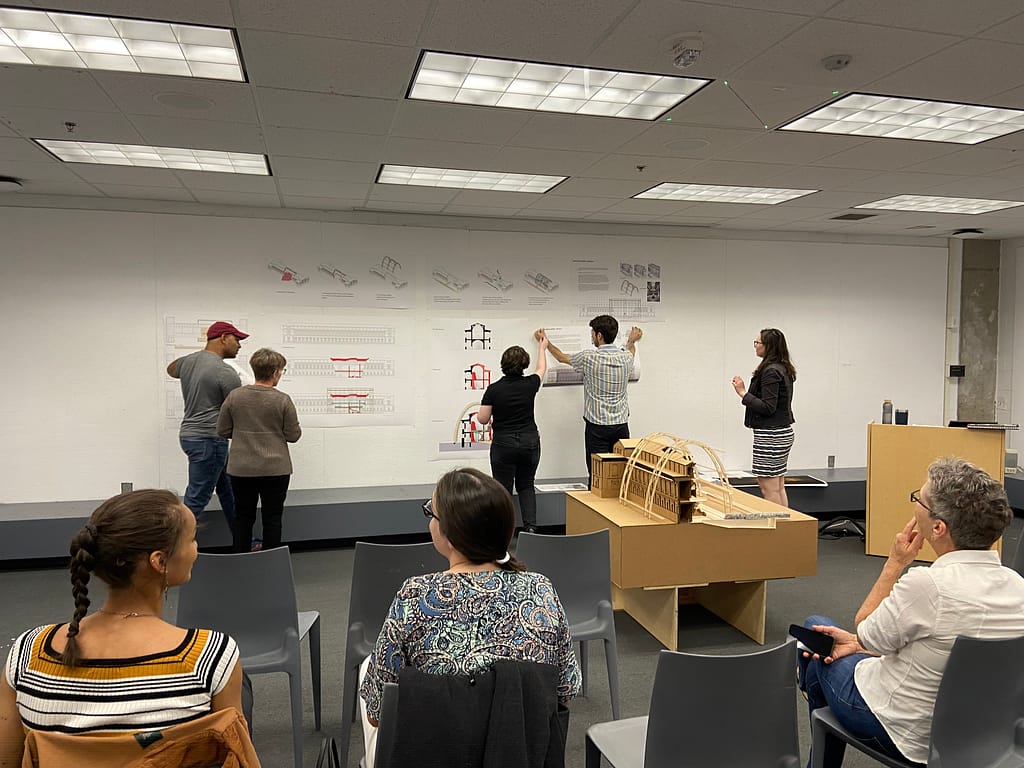

The pivotal moment was April 30th, the thesis defense, the culmination of my years’ work. A meticulously orchestrated event following weeks and months of preparation. Two weeks before, I had the necessary pre-defense scrutiny with my committee and they had to approve that I had enough done so that I could defend two weeks later. The day of the defense was so stressful. I had the room from 1:30pm to 3:30pm and I told everyone 2:00pm because I needed time to set it up. Of course, the professor in the room before me stayed until about 1:40 and if weren’t for my friends helping me, I would have never got everything up in time. I spent the morning bringing everything to the fourth floor (I was on the bottom floor) so it was ready outside of the room, and then frantically running around getting everything on the walls. I was hot and dehydrated. I started off shaky and then found a bit of a groove. I spoke for around 20-ish minutes and then was barraged with questions for the next forty-five. I’m thankful to everyone who came and watched it online.

But the stress was far from over. From the date of the defense, we have two weeks to electronically submit our thesis book. Between packing, moving out of my apartment and studio, focusing on final projects for neglected classes, and spending time with my family while they came down for graduation, I had to work on my thesis book revisions. On Sunday, May 12th, I left Blacksburg and a ten-hour journey later I was back in New York. I unpacked and begrudgingly attempted to work on thesis revisions. I had graduated, but I wasn’t yet free. Over the course of the next two days, I worked all day and night, up until 2am working on revisions. It had to be approved by my committee members before I could submit it. I submitted it on Tuesday evening, May 14th. Then, it had to be approved by the graduate school, who has two weeks for more revisions and then we have to resubmit. The deadline is mid-June, but because I was going away, it would be impossible for me to get them done. I reached out to the person in charge and she kindly said she would get them back to me as soon as possible. A couple of emails and phone calls later, on May 15th, I successfully submitted my thesis to the graduate school and it was approved. I could finally breathe a sigh of relief.

My thesis book can be viewed here on the graduate school ETD.

My first blog post last summer on thesis thoughts

All blog posts related to thesis

Thesis Defense Spoken Part

Below is the script that I used to present my thesis defense. Warning, it’s long.

To my committee for their guidance

To my family for their support

To my friends for their encouragement

To countless others who were a part of this journey

Thank you

War a perpetual shadow cast over human history, brings forth unparalleled destruction leaving behind a wake of devastation that scars both the land it’s people. It’s relentless march leaves cities in ruins, families torn, landscapes transformed and the built environment obliterated.

War affects an individual, a community and a country’s identity. Destruction both leaves a memory and shapes it. I will begin with an exploration of memory and its tie to place, I will then examine memorials and their role and ultimately, I’ll connect these themes with my project, which seeks to investigate these concepts through a series of interventions.

Lebbeus Woods outlined three principles that emerged from his research into post-WW2 reconstruction

The first principle: “Restore what has been lost to pre-war condition.” (erase the effects of war and move on)

The second principle: “Demolish the Damaged and destroyed buildings and build something entirely new.” (move on by forgetting the old)

The third principle: “The post-war city must create the new from the damaged old.” (new way of living)

During my research, I realized there might be a crucial, albeit often overlooked. It’s not a new principle of reconstruction, but rather one that was used post-WWII, although in much rarer instances and only with a select few buildings.

The fourth principle: Leave the demolished building as is in its ruined state. (memorialize the event)

Today,I’m proposing a fifth principle, which is to preserve the building in its ruined state, while utilizing remnants of the original building to guide new interventions. By re-purposing the destroyed section and space and imbuing it with a new way of interacting, a connection with the past event that led to its ruin becomes established. These interventions serve as a bridge between the past and the future. Transformation through remembrance.

First, I want to acknowledge the various ways in which the destruction of architecture can occur, whether by human actions or natural forces.

Demolition: When architecture is intentionally destroyed, typically to make room for new constructions, eliminate hazardous structures or renovate existing ones. This process is controlled and purposeful, serving specific objectives.

Nature: Architecture can succumb to the powerful forces of nature, such as hurricanes storms and floods. The damage inflicted can range from superficial, rendering buildings unsafe or completely destroyed.

Weathering: Over time, all architecture is subject to weathering, a gradual inevitable process of deterioration. From the moment it is built, it begins its journey toward its assured decay.

War: Architecture destroyed by conflicts suffers at deliberate and malicious destruction. This is distinct from controlled demolition. In war, buildings are specifically targeted, with the intention of inflicting harm.

Despite the diverse causes, the outcomes tend to be similar. What makes architecture destroyed by war distinctly different from the others?

Memory. War affects an individual, a community a country’s identity. Destruction both leaves a memory and shapes it.

Memory is indispensable for learning, adaptation and survival. It is also what ties us to our sense of place, our cultures and where we come from. The term Genius loci, “the spirit of the place” and the geographical/architectural concept of a “sense of place” both refer to the experiential and expressive aspects through which we perceive and interact with different locations. Architecture itself significantly contributes to the creation of a sense of place. As Hannah Arendt argues, “the reality and reliability of the human world rests primarily on the fact that we are surrounded by things more permanent that the activity by which they were produced.” The destruction of one’s environment, therefore, can lead to the loss of one’s collective memory and consequently have a disorienting effect on one’s life and connection to a place.

Throughout history, the destruction of architecture has accompanied the triumph of one civilization over another, as a form of oppression, or resulted from deliberate attacks on buildings and cities. These attacks have symbolic power in their own right, which is why strikes against them have been favored by terrorists when there is no direct military gain. The impact of September 11th stands as a personal testament. The twin towers not only symbolized New York City, but also represented the economic position of the United States. Their collapse had an immediate and profound effect on both the American and global psyche. Similar attacks on places of collective importance have occurred worldwide.

During WWII, carpet bombing campaigns were extensively carried out by both the Allied and Axis powers on cultural and civilian centers aimed to undermine citizens’ morale, and shatter their resilience. In Syria and Iraq, many of its ancient structures were deliberately demolished by ISIS as part of their campaign to erase pre-Islamic history. In Tibet, countless monasteries and traditional Tibetan homes and buildings have been demolished in a forced attempt to exert control over Tibetan culture and identity. The built environment and our architectural heritage is intricately connected. Architecture is the tangible expressions of a culture’s values, beliefs, traditions and way of life.

In the case of the World Trade Center, a new tower was rebuilt as a symbol of hope for the future, while its height of 1,776 feet serves as a historical tribute and remembrance of the past. The two lost buildings’ footprints were transformed into a memorial, preserving the memory of the event and the lives that were lost. Like phantom limbs, we can imagine the towers as they once stood, yet their absence remains as an enduring presence.

(Talk about 2 memorial competitions)

Memorials, like the world trade center serve as an anchor to the past, to the events that happened and to the people that were lost. It is a narrative of human experience ensuring that lessons from the past and people are not forgotten. They stand as tangible testaments, offering spaces for reflection, remembrance and reverence. Memorials embody collective memory and serve as touchstones for future generations. They bridge the chasm between past and present, allowing us to exist with one foot in each.

This memorial advocates for a ban on nuclear weapons, creating a memorial on a decommissioned nuclear weapon testing site. The memorial aims to immerse visitors in the powerful and devastating impact of a nuclear bomb. The width of the memorial corresponds to the blast radius and its height mirrors the detonating height in the atmosphere. Red clay rammed earth pillars rise from the ground, juxtaposing the human-made bomb. As one walks toward the center, visitors feel the blast effects on the pillars until reaching a central wasteland, conveying the gravity of nuclear devastation.

In February of 2011, the destruction of Christchurch occurred due to a series of earthquakes. The result was 185 fatalities.

The site for the memorial is located on the Avon River, a park/green space between Montreal Street bridge in the west and the bridge of Remembrance in the east. The memorial, symbolically and physically unites the two sides of the river and the city. A pedestrian path, adorned with 185 columns representing the 185 people who died, exist within and around the path. At night, these columns emit light, symbolizing the lost lives. The design not only pays tributes to the victims, but also creates a connected space for reflection.

It is in human nature to seek the restoration of architecture that has been destroyed. Often, the immediate response is to reconstruct the destroyed structure as was, as quickly as possible to suppress and erase the trauma of destruction by eliminating its visible scars. To erase the memory of the tragedy and loss is to erase the history of what happened.

Destruction manifests in various scales, demanding careful assessment before deciding on the approach to rebuilding. Complete destruction leaves limited options, either restore what has been lost to its pre-war condition, or demolish the damaged and build something entirely new. When a significant portion of the building remains intact and the destruction is limited, a unique opportunity arises to build upon the damaged form and introduce something new, balance the act of preservation with reinvention.

(Talk about Notre Dame competition)

In April of 2019 a fire tore through the wooden attic of Notre Dame. The wooden timbers known as “the forest” was beyond saving and the spire eventually collapsed. In the immediate aftermath, France’s President Emmanuel Macron launched an international architectural competition to redesign the spire, “giving the medieval building a spire suited to the techniques and challenges of our time.” Immediately, the French Senate passed a bill requiring the reconstruction be faithful to its “last known visual state” and aborted the competition, with plans to rebuild the spire as it was.

The fire created an opportunity to envision Notre Dame in a new light for future generation. The proponents for rebuilding it as it was, miss the dynamic aspect of a building over its lifetime. It prompts the question: which historical period should be preserved? France’s decision to rebuild the spire to its last known visual state is inherently flawed, considering the spire was a later addition by French architect Viollet-le-Duc, who reimagined Notre Dame in the 19th Century. Notably, the original spire contained 460 tons of toxic lead coating, raising questions about the accuracy of the last known visual state. Rebuilding solely to maintain a nostalgic fantasy undermines the purpose of the reconstruction process.

(quick critique)

In many instances after destruction, like Notre Dame, there is a strong urge to rebuild as quick as possible and as it once existed. In 1993, the Stari Most bridge in Bosnia and Herzegovina was destroyed and immediately calls for reconstructing the bridge identically began in 1994. After the pentagon was attacked in 2001, the government issued the Pheonix Project with the goal to reoccupy the outermost ring on September 11th 2002 a year from the initial attack. The Frauenkirche in Dresden was completely destroyed during WW2 and was rebuilt exactly as it once stood 23 years later. But is this always the best course of action? Instead of trying to recreate what already existed, create something new reminisce of what was.

(Talk about Alte Pinakothek)

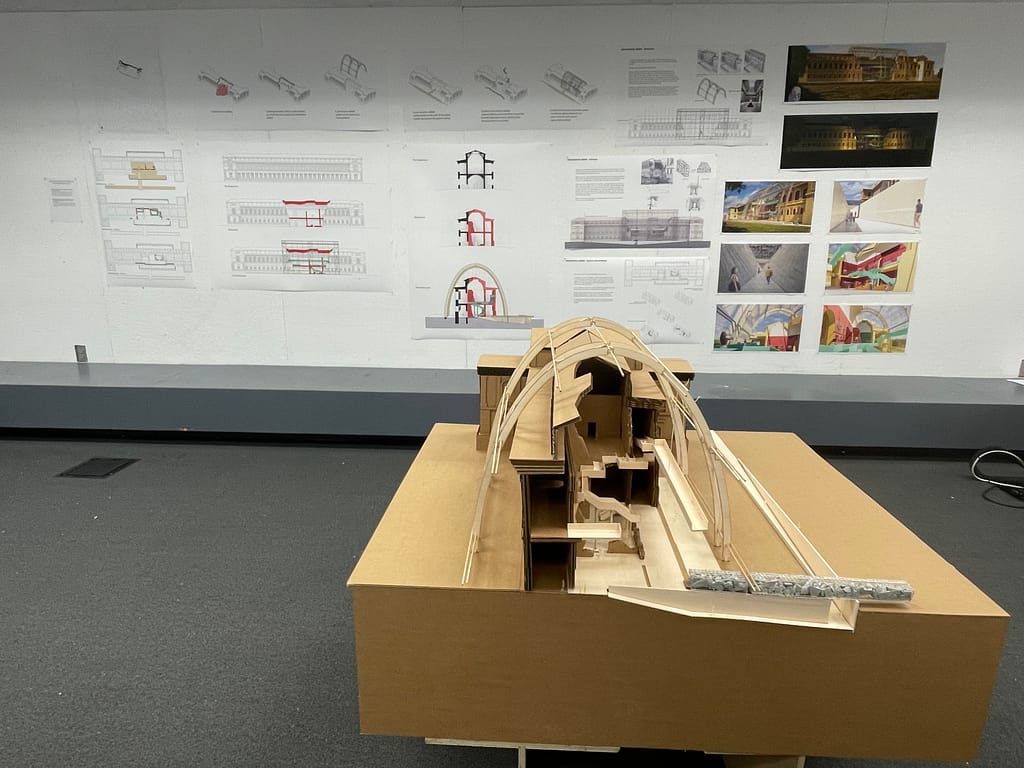

The site is the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, Germany. The Alte Pinkaothek is a museum, built in the mid 1800s and became a model for museums worldwide. It was partially destroyed during the bombings of WWII. It has since been rebuilt, for my thesis I’m using it as the object of my investigation.

Public buildings, like museums, play an important role in the built environment. Not only do they preserve the culture and heritage, holding objects that are culturally and historically significant, but the building itself becomes an important culturally significant object. They act as community spaces and hold the symbolic importance of civic pride and identity. The destruction of these buildings can have a significant impact on the community and the process of rebuilding after destruction due to war or attacks raises complex questions.

Examining this through the lens of my project, I’ve identified four stages of occurrence:

- The destruction happens

- The destruction is left as is and cleaned up to a degree

- Small structural support and stabilizing is done

- Interventions are added

The destruction happens

Destruction is a violent act. It doesn’t follow rules and it doesn’t care for what already exists. It’s unrelenting and it instantaneously changes the built environment. One second something is there, the next it is not, turned into a pile of smoke-filled rubble. When architects build, they build for the future; they account for live loads and dead loads, safety factors are multiplied 2,5,10 times to ensure the safety of a building, but there is no safety factor for explosive devices. Explosive devices tear through a building like they didn’t exist. Its guts exposed, turned inside out.

The destruction is left as is and cleaned up to a degree

Acknowledging the destruction, it is left as it is and cleaned up to a degree. A key moment frozen in time, the act of destruction and the damage done will become memorialized, enshrined so that future generations will not forget what happened. Cleaning up the space will make it inhabitable again. However, cleaning does not erase the physical evidence of the previous. Ghost traces of the former space, walls that leave a trace on both the ground and the ceiling, a scar varying in depth and thickness. Lina Wong states that preserving these is a “multidisciplinary interaction between repairing, conserving, restoring and recreating.” (from pg 136 Adaptive Reuse)

Small structural support and stabilizing is done

In order for the space to become safe, small structural support and stabilizing is done.

Interventions are added

Interventions are key to bringing life back into the destroyed space. There are three primary forms of interventions: enclosure, entryway, and interior interventions. The aim of these is twofold: to honor the building’s history and to let it serve as a compass for the new. These new interventions are meant to integrate within the existing space, offering visitors and new perspective while preserving the essence of what came before it.

The entryway

Destruction creates rubble. Debris from the building creates a path of destruction. As the aftermath is cleared away, the rubble finds a new purpose in a gabion ceiling, integrated into the redesigned entrance of the museum. The new entrance, which starts below ground level, follows a slow ascent along the bath of the rubble, culminating in the reclaimed space of destruction. Accessing the entrance involves a slow gentle decline, which gradually obstructs the museum from view. The smooth surface of the concrete walls and floor, punctuated only by the construction joints, sets the rhythm and serves as a contrast to the highly ornamented façade of the museum. At the bottom, the new museum entrance bisects the ramp. It is a sensory experience. The rubble-filled gabion ceiling lets dappled light into the space, giving the illusion of being buried while a striated concrete floor makes the visitor aware of the steps they are taking. As they walk through the space, the slight incline brings them closer to the gabion ceiling. As they ascend up the ramp the gabion ceiling abruptly ends and they emerge into the cavernous space of the destruction.

The enclosure

A structural arched enclosure, a glass curtain wall gives the destroyed section a crystalline translucence. A nod to the vaulted interior, the arched glass also reflects inward. The destruction is preserved, contained within. The glass curtain wall contrasts with the neo-classical façade, while also allowing those on the outside to see in and those within to see outside. The transparency serves to acknowledge the destruction, contained yet visible. The art that was adorned the walls re-adorns the wall and the transparency of the glass gives those on the outside glimpses of what’s on the inside. Bringing the interior of the museum to the exterior. The structure is meant to be unobtrusive so that the visual emphasis is on what’s within rather than what’s holding the glass curtain wall in place. The structural components of the arches are placed in intervals so that they correspond to the rhythm of the columns on the façade. The inherent properties of glass offer a dynamic interplay with sunlight, rendering the building’s appearance ever-changing. In moments of transparency, glimpses of the interior are revealed in appropriate solar conditions, or at night when the interior is respectfully lit. Other conditions will render the glass reflective, obscuring and the glass becomes a wall, an extension of the façade.

Interior Interventions

Inside, what used to be two spaces divide by floors, becomes one. A light filled sanctuary for the public. A place to be occupied and used. For families to gather, for friends to meet, or for tourists to rest. Providing memories of the event and of the building’s history, remnants of the former walls are left in their destroyed state while the fully destroyed ones can still be seen as an imprint on the floor. A newly added staircase serves as both a physical and symbolic connection between the divided spaces, juxtaposing the old and the new. Additionally, raised walkways bride the former areas, but also invite visitors to inhabit and perceive the space anew. They exist in the memories of the former building, following the paths of the doorways or walls that once existed. In occupying a space that once existed, visitors are compelled to engage in introspection and reflection, forging a deeper connection with the site’s narrative. “The past co-inhabits the space of the present without erasure or recriminations” (p.138 adaptive reuse).

The dialogue between old and new, achieved through a juxtaposition of materials, form and spatial arrangements can evoke a tension that honors both the historic structure and the scars it bears from its past damage.

War unfortunately continues to persist as a part of human nature. When I started my thesis, the war in Ukraine dominated global and U.S news cycles. As my thesis progressed, a new conflict erupted in Israel and Palestine and is currently ongoing as I write this. The imperative of rebuilding after such devastation is ever more pressing today. The initial step involves an analysis of the extent of destruction inflicted upon a building, structure, or the built environment.

This thesis attempts to propose one such approach to rebuilding: preserving the building in its ruined state, while utilizing remnants of the old to guide and inform the new. By enshrining the act of destruction and its damage, the memory of these events becomes immortalized for future generations. Interventions are key to bringing life back into the destroyed space. The aim of these are twofold: to honor the building’s history and to let it serve as a compass for the new. These new interventions are meant to integrate within the existing space, offering visitors a new perspective while preserving the essence of what came before it.

Architecture does not exist in isolation, but as a reflection of the people it serves. Therefore, the involvement of communities in the planning and rebuilding efforts is not only beneficial, but essential. Their intimate knowledge of the cultural heritage, and social dynamics inform decisions that resonate deeply with the collective identity and memory of the place. They are the ones who decide if something should be rebuilt, or left as it. Should it be enshrined or erased. Through participation, rebuilding becomes a collaborative endeavor, weaving together the threads of memory, remembrance, and hope, ensuring that the rebuilt environment belongs to its inhabitants.

Ultimately, this thesis aims to continue the larger discourse on the critical importance of post-conflict reconstruction. While the site in Munich, Germany served as the object my investigations, it also serves as a foundation for application in similar contexts.

Congrats Joe,

Well done!

Pingback: Four Days in Scotland: Castles, Culture, Cows and Charm: Four Days in Scotland - JourneymanJoe

Pingback: Visiting My Sister Santa Monica - JourneymanJoe