While the focus of my L.A. trip was visiting my sister, it’d be impossible not to include an architectural tour of the city while I was there. L.A. is a place where the built environment tells its own story.

In the mid-1900s, for example, the Case Study Houses were a series of modernist experiments commissioned by Arts & Architecture magazine. The idea was to design and build affordable, efficient homes for the postwar era, using new materials and construction methods. Some of the most iconic names in architecture, like Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, and Pierre Koenig contributed to the program, and their glass-and-steel houses have since become landmarks of California modernism. If you want an architectural book on this subject matter, check out the promptly titled book Case Study Houses.

At the same time, a black architect, Paul R. Williams was designing elegant, bespoke homes for Hollywood’s elite, all while facing racism and discrimination. He had to learn how to draw upside down because his white clients felt uncomfortable sitting next to him. He was known as the “architect to the stars,” and built a career that defied the era. If you’ve ever flown into L.A., you’ll see his contribution in the form of the 1961 space-age Theme Building at LAX.

California Modernism is just one layer, though. L.A. also has its Spanish Colonial revival roots, its Art Deco gems, and the space-age futuristic style. It’s a city of architectural contradictions and reinvention.

Architecture Books on L.A.

Countless books exist in an effort to understand the city and its architecture. Reyner Banham’s Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies frames the city not by neighborhoods but by the freeways, beaches, flatlands, and foothills that shape how people live there. There’s also Experimental Architecture in Los Angeles, which dives into the city’s constant pushing of boundaries, from lightweight structures to radical housing prototypes. And then Mike Davis’s City of Quartz looks at the social, political, and economic forces.

Santa Monica Architecture

One thing I really enjoyed was just walking around Santa Monica and taking in the architecture. The city is full of low-rise apartment buildings, each with its own uniqueness, some mid-century modern, some more Mediterranean-inspired, others just different. Because L.A. gets little rain, you see a lot of flat roofs, which give the buildings a different look. Flat roofs also open up more possibilities, like roof decks and outdoor spaces, making the buildings feel more connected to the weather. Outdoor courtyards were abundant in the architecture. It’s a place where even a random residential block or building can feel like its own little case study in style.

Architecture of the Visit:

1. Gehry Residence

Frank Gehry is probably the first architect I came to know. We had to do some type of research project in a high school art class and I remember I chose him after watching a documentary featuring him called Sketches of Frank Gehry. His 1978 Santa Monica home is still his current residence, or so they say. It is a deconstructivism icon, seemingly out of place amongst the typical suburban homes that surround it.

He used everyday items like chain-link fence, corrugated metal, and plywood to create the extension. It’s iconic and you can walk right up to as you could anyone’s home. Trick or treaters could knock on the door if they weren’t scared off by the unconventional material usage.

2. Schindler House

Rudolf Schindler’s 1922 West Hollywood house is often called the birthplace of California modernism. Its open plan, concrete walls, and emphasis on indoor-outdoor living redefined residential design in LA. It’s also a house that wouldn’t seem too out-of-place today, although it could do with some higher ceilings. Below is an excerpt from Architecture Today that can describe it better than I ever could:

“What he created does not, to put it mildly, lend itself easily to expository description. Pinwheel in plan, with multiple spokes protruding outward into the landscape, the Kings Road house is a confounding whirl of private and public, work spaces and social spaces, with garden courtyards penetrating inwards towards the central node. The planar and spatial complexity marks Schindler’s first assault on the plodding processional normalcy of the prevailing residential scene; the program presses the attack, breaking up the typical domestic arrangement with a two-family, communal living arrangement centered around a shared kitchen and dining space.”

I think that in order to fully appreciate the house, you have to understand the context in which it existed.

3. Levitated Mass & LACMA (Zumthor’s new museum, exterior)

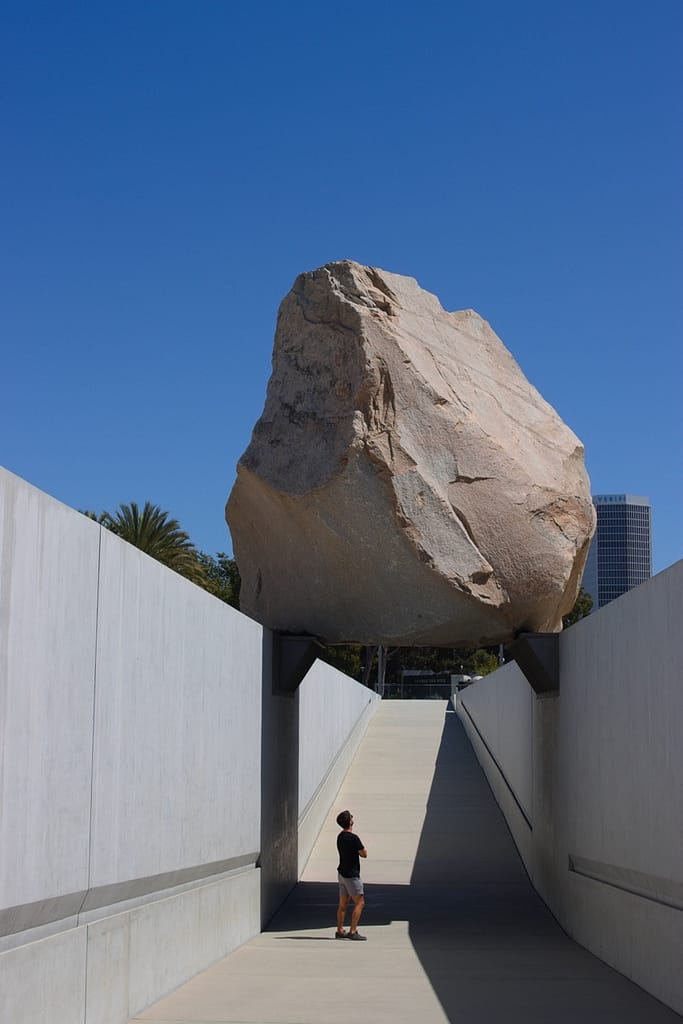

Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass, is a massive suspended boulder. The ramp and walkway underneath were the inspiration for the entrance to my graduate school thesis project. From the street, you can only see a portion of it and as we drove by it to find a parking spot, my sister said, “that’s it, that little thing!” Once we walked underneath it, she changed her mind. Next door, Peter Zumthor’s under-construction museum promises to reshape the Los Angeles County Museum of Art with bold, flowing forms.

4. Los Angeles County Museum of Art

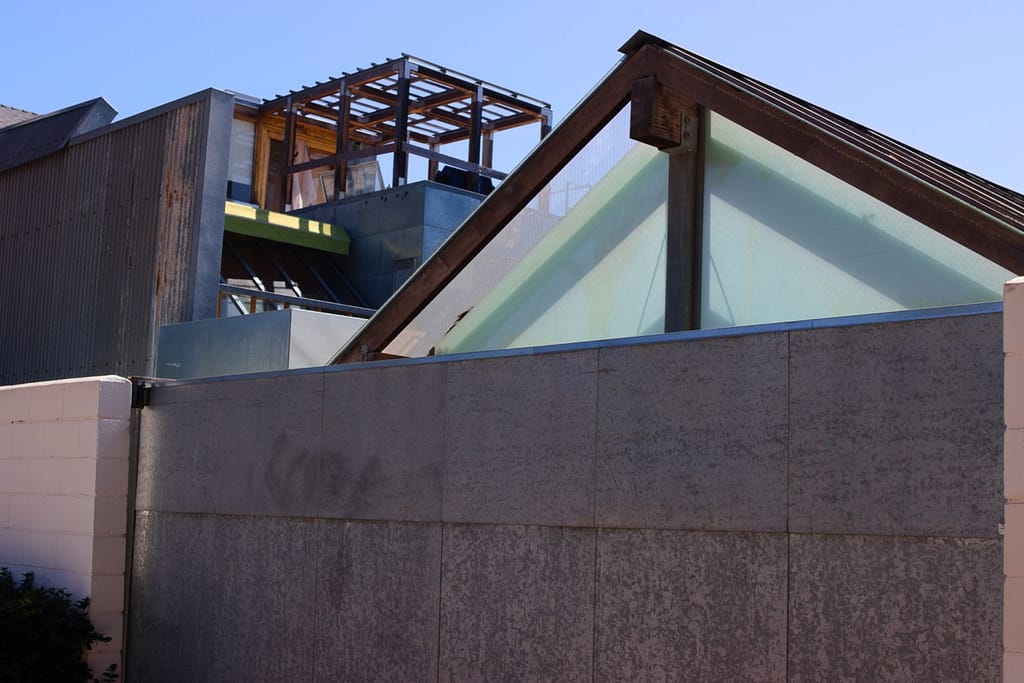

Right next to the Levitated Mass is the in-progress extension to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art by Peter Zumthor (check out my blog post visiting his work in Switzerland!). Peter Zumthor’s architecture was one of the main reasons for my Swiss visit last year. However, I’m not sure how I feel about this one, perhaps it has to be experienced from within when it opens.

I do know, it’s had its fair share of controversy, including costs and regulations that changed Zumthor’s original design intent. He is quoted saying, “There have been tough moments, when we had to reduce, reduce, reduce.” When asked after all the simplifying, which elements of the building will be recognizable as Zumthor details, he responded, “There are no Zumthor details anymore.” It will be his first U.S building and considering everything that’s happened, it may be his last.

5. Bradbury Building

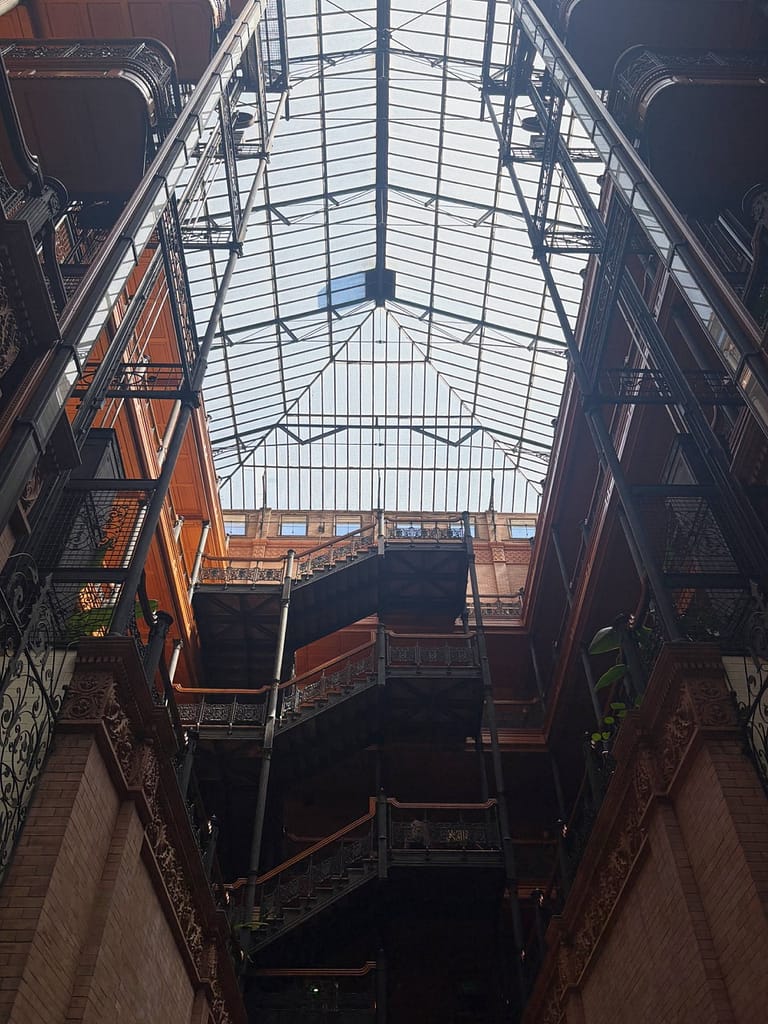

Built in 1893, this downtown LA building is famous for its interior ironwork, glass atrium, and intricate staircases, popularized in films like Blade Runner. “No cameras!” The guard yelled as I attempted to take a photo of the interior as soon as we stepped inside. Photos with the phone were okay though…

6. Westin Bonaventure Hotel

Designed by John Portman (1976), this mirrored-glass megastructure is pure late-modern hotel architecture. Its cylindrical towers, interior skybridges, and revolving rooftop lounge capture the futuristic ambitions of 1970s LA. John Portman is renowned for revolutionizing hotel lobby design by creating the modern soaring atrium. The Bonaventure hotel was astonishing. I wish I could have seen it in its glory when it was first constructed, filled with hotelgoers and full stores and restaurants. When we were there, it looked like shops and restaurants that circled the perimeter of the atrium had been closed for decades.

7. Walt Disney Concert Hall

Frank Gehry’s stainless steel masterpiece. It is a concert hall built in 2003, a cultural and architectural icon. Its sweeping, sculptural curves make it one of the most recognizable buildings in the city and my sister had the luck to see a concert from within! I was only able to walk around the exterior.

8. Broad Museum

Opened in 2015, Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Broad Museum is wrapped in a porous honeycomb “veil” that filters light into the galleries. It sits right next to Walt Disney Concert Hall and compliments it nicely.

9. Hollyhock House

Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1921 design for Aline Barnsdall combines Mayan Revival motifs with Wright’s Prairie style. It’s also LA’s first UNESCO World Heritage site and the first Frank Lloyd Wright House I have visited. It was absolutely amazing to experience. Unfortunately, we couldn’t tour the central courtyard area because of the heat. Here is the guide to get a more in depth look at the house.

The centerpiece of the house and one of the most magnificent features is the fireplace. For Frank Lloyd Wright, the hearth was the center of the home and the fireplace in the Hollyhock House makes a statement like none other I’ve seen. The relief area around it was meant to feature water (a common theme in his architecture), but due to plumbing issues it didn’t work properly.

We revere Frank Lloyd’s Wright architecture as architectural monuments, a representation of the genius who pioneered an architectural style and changed the way we build and live, however most of the people who he built homes for couldn’t stand to live in them. Who and what are we building for, if not the people who will inhabit them?

Aline Barnsdall left the Hollyhock House after a few months. She was unhappy with the house’s layout (which is surprising considering she and he went back and forth over the plans), the lack of ventilation and leaking that led to mildew and buckling floors. I believed she also complained about it being dark and when I was there on a very sunny L.A. day, the central living space did have a darkness to it.

According to many architectural historians, it was Schindler (of the Schindler House #2 above) who drew or refined many of the plans and supervised the construction of the house. He even convinced Richard Netura (of the Neutra VDL House #10 below) to come to L.A., where he stayed with him in the Schindler house for a few years (from Discover Hollywood).

10. Neutra VDL House

Richard Neutra’s 1932 Silver Lake residence doubled as his family home and architectural office. It was amazing. We went as a family, and I think everyone appreciated seeing this early 1900s masterpiece. It was light filled and airy, every decision representing intention behind it.

11. Griffith Observatory

My sister and I hiked to Griffith Observatory on one of the hottest days in L.A. On the way up I had my first glimpse of the Hollywood sign! The observatory was completed in 1935 in a mix of Art Deco and Greek Revival styles. We couldn’t go inside, but the observatory provided amazing viewpoints toward the rest of L.A.

12. Venice Canals

What an amazing surprise. I had no idea what the Venice canals were and never saw any photos of them. They’re a quirky pocket of architectural charm hidden in the heart of Venice. Each house represents a unique architectural style at the whims of those who inhabit them.

13.Giant Binoculars

The Giant Binoculars are a 45-foot by 44-foot by 18-foot structure in Venice incorporated into the building façade. It was created in 1991 by artists Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen. The binoculars are part of a building designed by Frank Gehry and act as the entrance as well as a functional architectural element housing a conference room within. They are a quintessential example of postmodern architecture, a playful example blurring the lines between art, architecture and everyday objects. They are right on the main road to Santa Monica from Venice, we had probably passed them a couple of times (without knowing) before deciding to go to them and my sister in her two years of living there has driven past it many times without ever noticing them!

14. Venice Skatepark

While not quite architecture in the traditional sense, it falls under the umbrella of landscape design and public spaces. A skatepark is a form of a plaza and the Venice skatepark is where hundreds of people congregate. Most are observers watching the brave few on skateboards or rollerblades navigate the parks obstacles. I couldn’t imagine doing a hobby for fun with that many people watching.

15. Santa Monica Pier

Santa Monica Pier, the end of Route 66 was built in the early 1900s. It juts out 1,600 feet into the Pacific Ocean and offers beautiful views of the Santa Monica coastline. It’s like a bare minimum amusement park with a roller coaster, Ferris wheel, a ride for smaller kids, some amusement park-style games and a place or two where you can get funnel cake or ice cream. We went on the rollercoaster and it was quite fun. At the end of the boardwalk is a restaurant and while we didn’t eat there, it would be an amazing place to catch a sunset.

16. Sunken City (San Pedro)

Initially not in our trip. At the planning phase I discounted the Sunken City because it didn’t look like much, and it wasn’t anywhere near where we were going. However, we ended up nearby on our way to a beach and I’m glad we went because it was unexpectedly beautiful. It is the remains of a 1920s neighborhood that slid into the ocean after a landslide. The ruins are tilted sidewalks, broken foundations, and graffiti-covered fragments. It sits on a bluff next to the ocean, the brightly colored graffiti adds a touch of unexpected color to a natural landscape palette.