A trip to Switzerland wouldn’t be complete without seeing the work of Peter Zumthor. Peter Zumthor is a Swiss architect renowned for his restrained, material-focused designs. He was born in 1943 and worked as a cabinetmaker before studying architecture and design. Because of this, his work is deeply rooted in craftmanship, with a strong emphasizes on how things come together–moments of joinery are celebrated throughout his work. In 2009, he was awarded the Pritzker Prize, the highest honor for architects. Despite his global recognition, he only has completed only around twenty built projects and is known for his selectivity. He doesn’t even have a website, a stark contrast to someone like Frank Gehry, another Pritzker Prize winner, who has more than seventy built projects around the world, and a website (albeit a not very good one though).

Chur

Chur is located in eastern Switzerland only about an hour and a half from Zurich by train. It is the oldest city in the country. It is a small city of about 41,000, but boasts a rich history, beautiful architecture and acts as a gateway to the Swiss Alps – it is the starting point for the famous Bernina Express train through the Alps and into Italy. It is also home to one of Peter Zumthor’s first projects, the Shelter for Roman Ruins, and a close proximity to some of his others; the Thermal Baths in Vals, Switzerland, the Saint Benedict Chapel in Sumvitg, Switzerland, the Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria, and his studio, located in the town north of Chur. There is also a beautiful concrete bridge nearby Chur, which made it was the perfect starting point for my Zumthor pilgrimage.

Swiss trains are fantastic. It is a small country and it’s easy to get to almost anywhere in the country via train. Because of this, once in Chur, I assumed I could use public transport to visit all of Zumthor’s works. I did extensive research googling distances and times it would take from one place to another and it all seemed possible. I couldn’t have been more wrong. When I arrived at my hostel in Chur–an interesting place housed in a former prison, the dorm doors reused as the previous prison doors–I chatted with the hostel receptionist, telling him about my plans. He mentioned that I should probably rent a car because it wouldn’t be possible to see everything I wanted to use public transport. Renting a car hadn’t even crossed my mind, but I quickly realized he was right, and it was the only way to make it all work, so I did.

Driving Around Switzerland

I rented a car through Europcar for two days and paid 189.45 Swiss Franc or 225.26 USD. Switzerland isn’t cheap. A five-day car rental in Puerto Rico cost me the same price. However, I did get a fantastic car. I was lucky enough to get a brand-new Seat Cupra Formentor, a performance-oriented coupe SUV that was a joy to drive around and navigate through the Swiss mountainous landscape. I felt like I could climb any mountain, something I definitely needed, unlike my eventful experience driving in Greece.

Driving in Switzerland was breathtaking. Chur is nestled at the base of the alps, so even in June, snow-caped mountains surrounded me everywhere I went. It was a challenge to keep my eyes on the road and not get distracted by the views, though I had to, for fear of accidentally driving off the narrow, winding roads.

Many of the roads are not wide enough for two cars to pass comfortably and they feature a lot of blind curves with no way of knowing what was coming around the corner. I had one close call with a bus that materialized out of nowhere. As I was making my way down an s-curve-shaped road, I was able to see cars coming up, or so I thought, as I got close to the 270-degree curve, I didn’t stay as close to the outside as I should have. The bus must have been well positioned because I didn’t see it coming, and as I was making around the curve, it appeared. Luckily, I had stayed far enough to the outside that nothing happened.

I also got a parking ticket. I couldn’t understand the parking rules, particularly what time I could park in the lot until. I was told it was free until a certain time, maybe 8:00, and I had an app that I could add time too, however, at 8:00 when I went to pay, it showed that I didn’t have to pay, so I thought the meter would start at 9:00. When I went to the car that morning, I had a ticket on the windshield. But, in true Swiss fashion, it was the most beautiful parking ticket I’ve ever seen (I haven’t gotten many in my life). It was printed on a high quality, somewhat thick piece of paper, with a shiny red stripe on the left side. Even the parking tickets reflect their attention to design.

Peter Zumthor and His Work

The Shelter for Roman Ruins

Zumthor’s Shelter for Roman Ruins is in Chur. It is located just a short walk away from the train station, just on the outskirts of the small city. It is a beautiful, restrained structure that was designed to protect and showcase the remains of a Roman archaeological site. It was completed in 1986 and features a wooden framework with a metal roof. The framework is permeable and acts as a protective area from the elements but allows for air to pass through, creating a connection with the outside. While it’s an enclosed space, it’s not sealed, creating a delicate interplay between shelter and exposure.

Zumthor uses a restrained pallet of timber, glass and metal. The use of timber harmonizes the building with its surroundings and connects to Switzerland’s historic use of timber in construction (like a lot of Zumthor’s work). Glass is used thoughtfully in two places, as two large square windows that allow passersby to catch a glimpse of what’s inside, and in the skylights that bring light in from above. Metal is used in the corrugated metal roof, which provides a nice contrast with the wood and stone of the ruins, and it’s used in the raised catwalk that allows you to walk through the space. It is also used in the stairs that hover just above the ground, not touching it. The separation between the ground of the ruins and the new construction that doesn’t touch it creates a powerful differentiation between the two spaces. Together, these materials create a balance between protection and harmonizing with the existing Roman ruins.

Therme Vals (Thermal Baths)

Zumthor’s Thermal Baths is in Vals, about an hour’s drive from Chur and through some of the most breathtaking landscapes I have driven through. The winding road is flanked by giant waterfalls cascading down the mountainside, vanishing into the depths below, while snowcapped peaks are ever present in the distance. Vals itself is nestled in a valley, flanked by majestic mountains on either side, with a grand waterfall acting as the doorman welcoming guests in.

The thermal baths were completed in 1996. They are amazing, a complete meditative and sensory experience. Built into a hillside, the structure is made almost entirely of a grayish, black, locally quarried quartzite stone, giving it a monolithic, timeless quality. Zumthor uses light masterfully, like any other material, another in his repertoire. You aren’t allowed to take photos of the interior, so I only have a few of the exterior, but I did a sketch of the interior as that is allowed. The cost is 70 CHF on Monday and Tuesday (15 CHF cheaper than Wednesday to Sunday) which is about $80 USD, and you are allowed to stay as long as you want. I stayed for around 4 hours and could have stayed longer, but I had another project of his I wanted to see and it was about an hour’s drive away. In order to go to the baths, you have to book your time slot in advance and they start at 11:00 and continue for 10-15-minute intervals. Here is the website that offers some interior views.

“Mountain, stone, water–building in the stone, building with the stone, into the mountain, building out of the mountain, being inside the mountain–how can the implications and the sensuality of the association of these words be interpreted, architecturally?”

Peter Zumthor

The Thermal Baths were one of the most amazing places I’ve visited. From the moment you pass through turnstiles to when you exist, you feel as if you’ve been transported to another world. The journey begins with the changing rooms. After passing through the turnstile, you turn left and find yourself in a long corridor. On the right, water flows out of the wall in several spigot-like fountains, rust-colored from where the water has been falling for decades, while the changing rooms are on the left. Not realizing there were separate men’s and women’s changing rooms (the signs weren’t in English and just said changing rooms), I mistakenly found myself in the women’s changing room. It must have been a surprise for the one woman who walked in (I had my clothes on) while I was there. She said “women’s?”, in a tone that I mistook for a question. I shrugged, indicating that I didn’t know. It was only after she left a few moments later that I realized she wasn’t asking me, but rather telling me. I quickly removed myself and my stuff and walked further down the hall to the men’s changing room.

Exploring the baths is an experience of constant discovery. Hidden within the negative spaces of the blocks were spa rooms of various temperatures, dimensions, ceiling heights and sounds. Some of the rooms are waterless, featuring lounge chairs and openings that look out to the valley. Time flowed as if it didn’t exist while I wandered between the various pools and rooms, alternating between states of sleep and exploration. My only regret is that I didn’t have someone to share the experience with.

Kunsthaus Bregenz

Zumthor’s Kuntshaus Bregenz is a contemporary art museum located in Bregenz, Austria and was completed in 1997. Bregenz is located about an hour‘s drive from Chur. In the morning, I stopped at Salginatobel Bridge, a stunning reinforced concrete arched bridge designed by Robert Maillard in 1929, voted as one of the world’s most beautiful bridges, and a quick stop into Lichtenstein, which doesn’t really have much to see. By one o’clock I was in Austria.

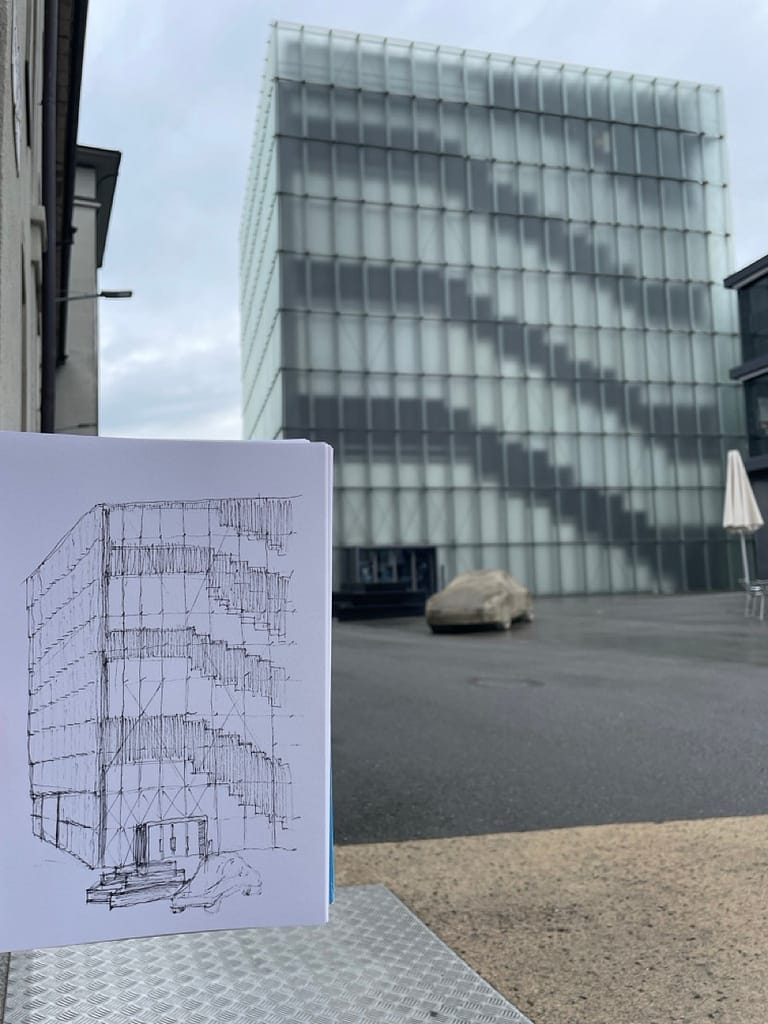

The Kunsthaus is renowned for its light-filled design, with a facade composed of frosted glass panels that subtly brings in and diffuse light into its spaces. It appears like an ephemeral object in the city, shifting with the conditions of the sun and clouds. It was a building I had seen many times over the course of my graduate studies in a multitude of classes. I saw various images of the building throughout my three years projected on the walls. I studied the wall details in depth and sketched how it came together, forming an intimate knowledge of the building. Seeing it in person was like meeting your idol.

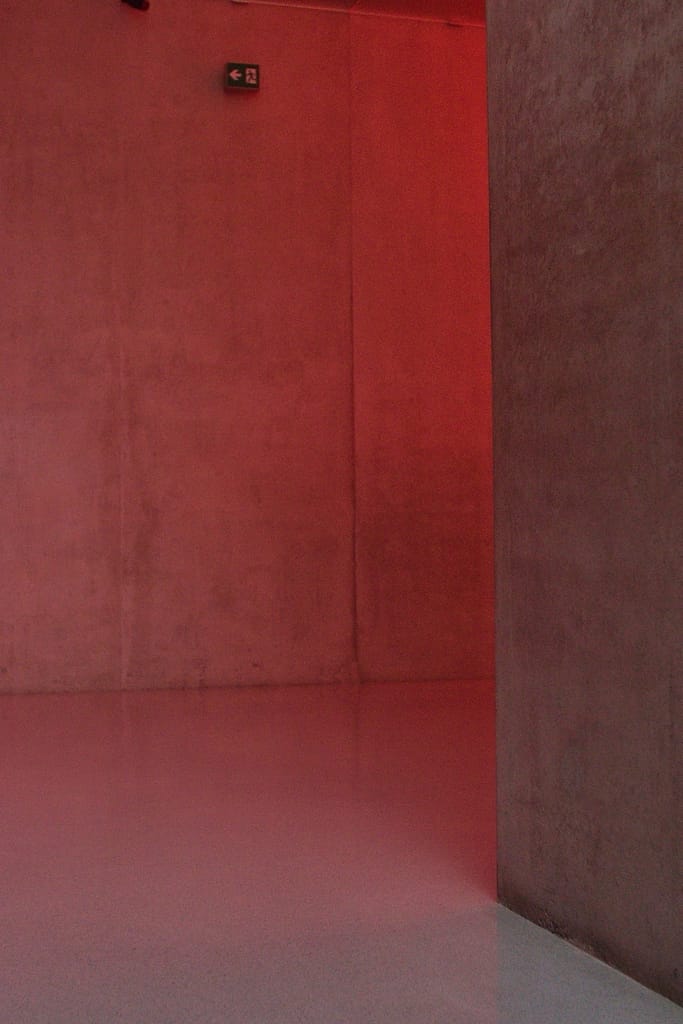

They say never to meet your idol because it can lead to disappointment. Visiting the Kunsthaus was indeed a letdown, but not because of the building–it was the exhibit. The temporary exhibit was by Anne Imhof, and while it was interesting and very impactful (after having the museum attendants explain it to me), it took away the most unique aspect of the building and the one I went to see. Instead of the soft, natural light filtering through the glass façade and casting delicate light into the space, it used red and white artificial lighting. While exploring, I made friends with one of the attendants and she temporarily shut off the red artificial light of the gallery, so that I could see into the ceiling above. It was brief, but gave me a glimpse behind the panels, one I assume few people get to see.

Zumthor’s Architecture Studio

Zumthor’s architecture studio is in Haldenstein, a small village about 10-15 minutes north of Chur. It’s tucked amongst the medieval alleys of the town and set against the backdrop of a mountain. From what I could see from the road, the studio is a synthesis of old and new, it’s two buildings, an existing structure or house expanded for his architectural studio. The material pallet consists of concrete, wood, glass and steel cables.

What’s remarkable is that despite being a Pritzker Prize winning architect, the highest honor in the field, his studio remains in a quiet, rural village in the eastern corner of Switzerland. A studio with no website and his preference for solitude.

Here is an article in Dezeen I came across, where he says, “I’m trying to change my mysterious reputation.”

Saint Benedict Chapel

Zumthor’s Saint Benedict Chapel is a tiny mountaintop chapel, located about an hour from both Thermal Vals and Chur, in the small village of Sumvitg. It was built in 1988 and replaces the former chapel of Saint Benedict, a stone chapel that was destroyed by an avalanche. The new chapel is down the road from the original, in a what I can only assume is an area more protected from future avalanches. It sits surrounded by a forest on its backside (up the mountain). After all, if an avalanche had already destroyed the former baroque-style chapel, it’s possible that an avalanche could come again.

In contrast to the original, Zumthor’s chapel harmoniously blends with its alpine surroundings. It’s a small wooden chapel, adorned with timber cladding, that references the local tradition of houses in the region. Its design emphasizes natural materials and craftsmanship. The water droplet shape of the roof and floor is its most defining characteristic and for such a unique shape, it doesn’t feel at all out of place.

The interior is minimal, aside from the wood columns and beams that support the roof, it consists of a few benches, a couple of rectangular closets in the back for storage, and religious icon framed in metal at the front. Light pours in through the upper windows, creating a serene atmosphere for reflection and an awareness of the passage of time. The building embodies Zumthor’s focus on materiality, place and the sensory experience of space.

GREAT!!

Pingback: The Architecture of L.A. - JourneymanJoe