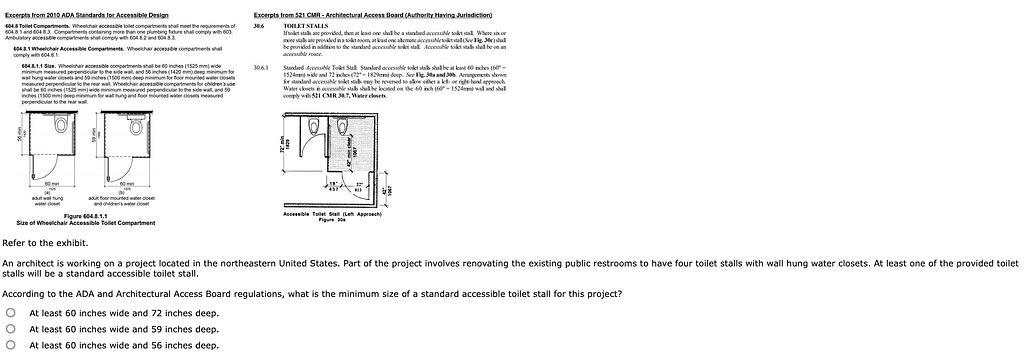

Over the course of two weeks, from May 2nd to May 11th, I took six exams spread out across two weekends (Friday, Saturday, Sunday, then again the next Friday, Saturday, Sunday). 24 hours and 20 minutes of testing. I passed four and failed two exams for architect licensure.

339 hours and 35 minutes, plus another 50 hours or more that I didn’t track across 100 days. Averaging 3.5 hours per day, non-stop without a break for 13 and a half weeks. It was exhausting. I put everything I had into it.

I would have loved if I could have passed them all on the first try so I could put this behind me, regain a portion of my life back and move on to other things, but I didn’t. The percentage of people who pass all six exams on the first attempt is around 2% and the average time it takes to pass all of them is around three years. I’m proud of the work I put in and the exams I passed.

Studying

Since February 1st, studying completely consumed me. Every single day for those 100 days until my last exam on May 11th, I studied. It was a roller coaster of emotions and an extreme investment of my time. I was determined. I had a lot to learn. I set a goal to attempt all six exams by May, and I was going to make it happen.

The Amber Book, a monolith of a course, had hours of videos and practice questions. That first weekend alone, I studied for 12.5 hours. By the end of the first week, I had studied 28 hours and 55 minutes. In the first month, I studied around 95 hours. The second month: 97 hours. And in the third month, around 109 hours. There were countless hours I didn’t log where I would be listening to something while working or walking.

When I first started studying, it felt good. It was empowering to take a step toward licensure. From the onset, I noticed how much studying was helping me become better at my job. Concepts started to make sense and processes and terms that I had only heard about in passing became applicable.

I began to understand things I’d previously just accepted without fully grasping, like the mini-split HVAC system we were putting into a project, or why you can’t just randomly add divisions to the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) MasterFormat. No one had explained that to me before. I didn’t even know what MasterFormat was until I started studying.

That gap between what architecture schools teach and what the profession expects you to know on the job is a common debate within the profession. Schools focus on design, theory and conceptual thinking and tend to focus less on practical, technical and professional knowledge. The profession, unfortunately, is very much akin to medieval trade guilds apprenticeships. Even if someone has no immediate plans to take the AREs after graduating, I’d still encourage them to start studying. It deepens your understanding, makes you better at your job, and puts you in a position to contribute more.

Study Schedule

I studied using the Amber Book, fitting it in whenever and wherever I could. As a former VT student, I got two months free, which was a huge help. After that, though, it jumps to about $250 a month, and unfortunately, I didn’t have any access to free study materials. By the time my two free months ended, I had finished the full course and taken all the practice exams. I really didn’t want to have to pay for a full month, only to review. I hoped I took good enough notes to review.

The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice (AHPP) is considered the Bible for three of the exams. Amber Book pulls content from it, but I still felt the need to read it. It’s massive, 1,200 pages of dense, practice-based material written in the format of a professional manual. Because each section is authored by a different professional, it often repeats itself or even contradicts other parts, which makes it harder to get through and to study from.

I read it bit by bit every night, usually about 30 minutes, and eventually finished it on April 10th, about two and a half months later. I don’t think it’s necessary if you’re already using the Amber Book. I also think it’s absurd that such a huge portion of the content for two of the six exams comes from this one book.

In addition to the AHPP, I read through the Architect’s Studio Companion, Building Construction Illustrated, Building Codes Illustrated (not fully, more like perused through it), and Sun, Wind & Light. Amber Book claims you don’t need any other materials, but I think it’s important to have the same information presented by different sources so that you can become more accustomed to it. Plus, it’s nice to take a break from staring at a screen and look at a diagram or a wall section on paper.

About a couple weeks into my studying, I started joining Amber Book’s online Thursday session at 6:00 PM called 40 Minutes of Competence (free). I also attended the Tuesday study sessions hosted by AIA NY (not free).

Once I finished the main portion of the Amber Book, I started taking practice exams. For seven weeks leading up to the first test, I took a practice exam every Saturday and Sunday. At first, I worked through the Amber Book’s practice exams. Then, over the next few weeks, I switched to the NCARB ones.

I failed every NCARB practice exam, some by a little, others by a lot, especially PjM and PcM. To pass those practice exams, you need to score over 71%, but on the actual exams, the passing threshold ranges from about 65% to 71%, depending on the exam and the exam section. Still, failing all the practice tests didn’t exactly boost my confidence heading into the real thing, especially since the Amber Book exams made me feel more hopeful. They were much easier, and while they tried to mimic NCARB’s question style, they never quite captured the complexity or feel of the real exams.

An example of my weekday study schedule:

7:40 – 7:55 walk to train station

8:00 – 8:40 study on the train, with a transfer at Jamaica

12:30 – 13:30 study while having lunch

18:45 – 19:25 study on the train back home (no transfer)

19:25 – 19:40 walk or get a ride home (in winter)

19:45 – 20:15 read AHPP while eating

20:15 – 21:00 Amber book

Taking the Exams

Project Management (PjM)

Practice Management (PcM)

Construction Evaluation (CE)

Programming & Analysis (PA)

Project Planning & Design (PPD)

Project Design & Development (PDD)

I scheduled the exams to take remotely at home, in the reverse order that is recommended by most. Most people recommend taking them PjM, PcM, CE, PA, PPD, PDD with the last three considered to be the most difficult and the longest. Both PPD and PDD are 4 hours and 5 minutes, while the others are 3 hours. PA, PPD and PDD are about constructing and building while PjM, PcM and CE are about the practice. When I scheduled them, I felt more confident with the building part.

Every weekend I took the practice exams, I took them at 10am because that was the time I had scheduled the actual exams and I wanted the practice exams to mimic the real exams, so that when I took the real ones, it wouldn’t feel any different. I thought that by taking it at home I could control the variables, like my comfortability, screen size, computer chair, mouse (I have a silent mouse), keyboard (silent keyboard) and I had good lighting in the room. The only thing I couldn’t control was what was happening outside, like gardeners making noise and that did make me nervous because as the weather got warmer they seemed to be out every day.

Remote Testing

One thing I didn’t expect was just how awful the remote testing software would be. If you’re thinking about taking these exams, do yourself a favor—go to a testing center. I wouldn’t recommend the remote option to anyone.

Before my first exam, I scheduled a 30-minute systems check with the exam provider, PSI, to make sure everything checked out. My internet connection, external webcam, and computer all passed the tests, so I felt good about exam day. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

The day of the exam, the software lagged constantly. I had delays opening the on-screen whiteboard and calculator (no scratch paper or external calculator is allowed), and the PDFs for the 10–15 case study questions loaded horribly slow. I probably lost around 20 minutes or more just waiting for things to respond.

Worse than that, I kept getting kicked out of the exam. Six or seven times per test. Every time it happened, I had to go through the entire check-in process again: showing all four walls of the room, the ceiling, the floor, under the desk, under the mouse and keyboard (they had to be external), my ears (to prove nothing was in them), glasses (to prove they weren’t smart glasses), and wrists (to show nothing was on them). I understand why, but it was draining. Especially when they’d ask me to show under the mouse pad and I would respond, I don’t have a mouse pad and they ask again, show under the mouse pad and again I’d respond I don’t have a mouse pad.

The first time it happened, 20 questions in the first exam, I panicked. I didn’t know what to do, I didn’t read about people having connectivity problems anywhere. As I went through the process to get back in, all I could think was that the clock was running. They say you get about 2 minutes per standard question and 4 minutes per case study question, and I was mentally tallying the time I was losing. It took 35 minutes to get back in. I was sure I’d lost 18 questions. How was I going to make that up and still pass? Thankfully, when I got back in, the time hadn’t moved. But that didn’t help my focus. Every subsequent drop disrupted my focus and increased my stress as I went through the check-in process for the fifth, sixth, seventh, time.

On one of the exams, I got kicked out with only three questions left. I was internally crying, begging the testing gods to just let me finish. Instead of the 4 hours 45 minutes the exam should have taken, it ended up taken me close to seven hours. I didn’t pass that one.

A week and a half before I was scheduled to take the exams, I got sick. I don’t know if it was the stress followed by months of studying, the pressure of having to take the exams, or the change in seasons as winter turned into spring. I’ve found that I usually get sick during this transitional period. It could have also been a combination of everything. Also, the day before the second week of exams, I started getting sick again. I felt like I was catching a fever and I was extremely tired, but I had three exams to take, so I had to push through.

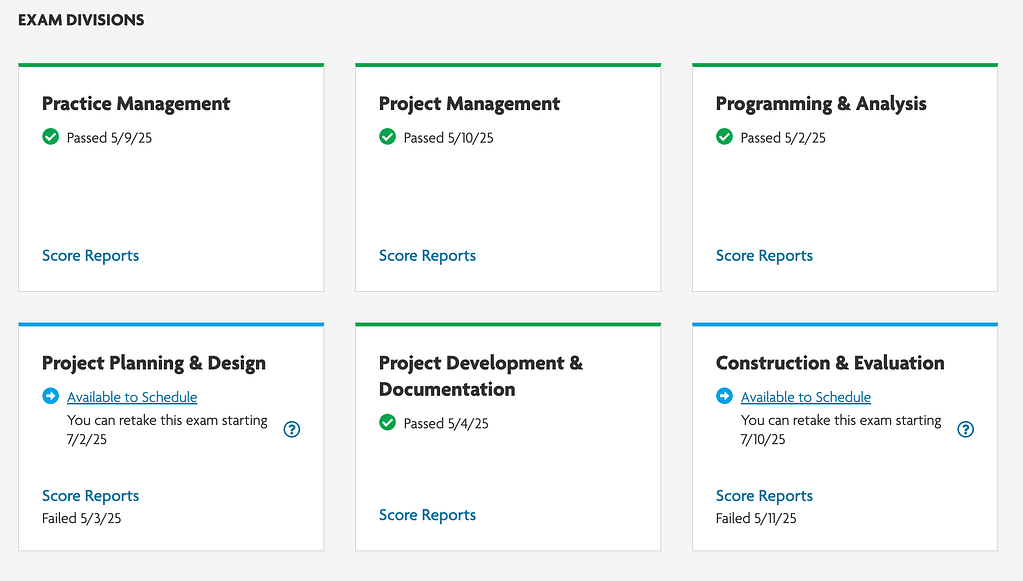

The Exam

The exam is entirely on the computer. It consists of three types of questions, multiple choice, check all that apply (you pick two, three or four out of six) and you have to pick them all correctly otherwise you don’t get a point and hotspot questions, where you have to click in the correct spot somewhere on the diagram or photo. Each question is worth one point. You can navigate to any question you want, but if you go on break, you can’t go back to any question you’ve seen, even if you didn’t answer it. So, when you go on break you have to make sure you answered any questions you opened. Time-wise is breaks down to about 2 minutes per normal question, and four minutes per case study question. Each exam has two case studies which involve a series of documents that you have to use to answer the questions.

At the end of each exam, there’s a button in the lower-left corner of the screen that says “End Exam.” When you click it, nothing happens at first, not for maybe seven seconds, but long enough to feel like minutes. Every single time I pressed it, I thought, “should I click it again?” And then, suddenly, in huge letters across the screen, either PASS or FAIL appears. It’s incredibly nerve wracking.

The first time I saw PASS, I couldn’t believe it. I was so relieved, I thought I had failed. Honestly, I felt that way after almost every exam, except Practice Management. That final moment of clicking the button never got easier. You have no choice but to do it.

Seeing PASS was a relief each time. My heart raced with excitement. It felt like all the hours and effort I’d poured into studying had been validated in a single word. But the FAILs, hit hard. Part of me felt like I could have passed them all on the first try. Why wouldn’t I think I could? Failing means doing it all over again. Studying, hopefully less intense now that it’s only two. Paying again. Each retake costs $250, and you have to wait two months before you’re allowed to try again.

The Results

Pass results just say pass, but fails give you a report card with an arbitrary number out of 800 that doesn’t correspond as a percentage to how many you got right. It’s more like the SATs. Luckily, the Amber Book has a conversion calculator that lets you know how well you actually did.

PPD – I scored a 66%, to pass you need between 65-71%. I mentioned earlier that the passing rate is a range depending on the exam. Based on my results, I only failed by a couple of questions.

CE – I scored a 64.11%, to pass you need between 58-65%. I failed by only one question.

It’s frustrating knowing how close I was, but on the other hand, the exams I passed could have been by one or two questions. I will never know.

The Costs

Before I could even schedule the exams, I had to register to get licensed in NY. To maintain licensure, there is a fee and I believe the fee below is for the first couple of years. Studying for and taking the exams is not cheap. Below are my costs for this first round of studying and taking the exams. Each exam is $250.

AHPP book $200

Building codes illustrated $52

Bic Multi-Color pens $30

AIA NY sessions $50

NY Licensure Registration $400

Exam costs $1500

Architects Studio Companion $67

External webcam $22 (wish I could return it because now I have this pointless external webcam, it was needed for at-home testing)Ethernet cable $60 (returned after it didn’t help me with my connectivity issues)

Total costs = $2,321

My previous post about when I decided to take them: On the Path to Architect Licensure: The AREs