La Tourette

To truly understand La Tourette is to experience it from within. To only view it from the outside would lead to misunderstanding. Upon first glance, La Tourette seems to be in disharmony with the landscape, a giant concrete monolith whose presence is undeniable. Yet, beneath this imposing façade, it possesses a subtle and balanced elegance aimed at making anyone who visits, not only aware of themselves, but of the surrounding landscape and the passing of time. It is a 20th century icon.

La Tourette, was built as a place of solitude, worship, study and contemplation for the Dominican monks. I stayed a night and attempted to find what the Dominicans themselves were searching for. Would I find my own spiritual retreat, a sense of peace and reflection within its concrete walls?

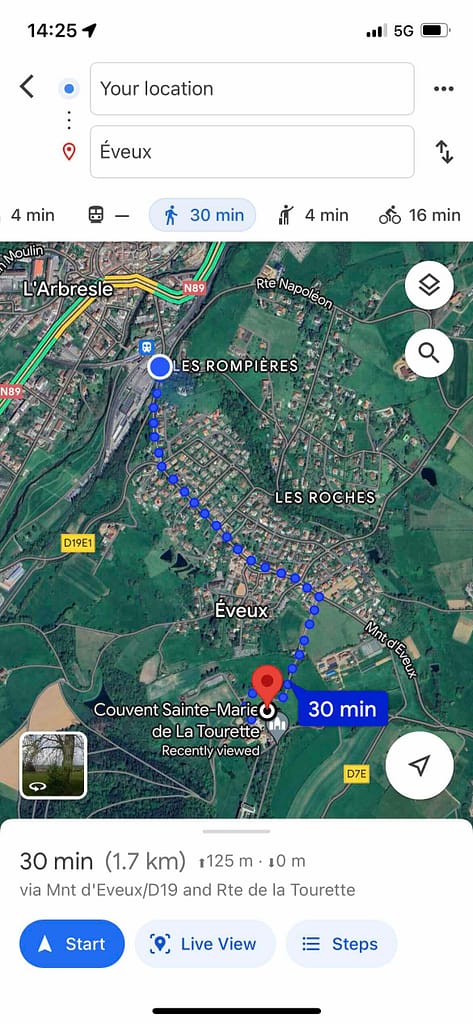

Getting There

La Tourette is located in the small village of L’Arbresle, about a forty minutes train ride from Lyon. I spent the night before in Lyon so that I could make my way to the monastery in the afternoon. The day before, I made my way from Lucerne, after stopping in Lausanne, Switzerland. It was quite the journey to get to La Tourette and during the planning stage of my trip, I often questioned whether it was worth it to spend the time and money to make this detour. Lyon wasn’t exactly on the way to anything and afterwards I had to double back to Zurich so that I could make my way to eastern Switzerland. It was a pilgrimage.

Once I arrived in L’Arbresle, the final leg of the pilgrimage began. Reaching the monastery required a 30-or so-minute steep uphill hike. That morning, I had already spent it walking through the medieval streets of Lyon. I was a month into my travels, averaging 18,900 steps a day and I had my two backpacks filled with everything I was carrying for the trip.

The town was quiet as I made my way up the mountain. I longed for the one or two cars that passed me to stop and say, “La Tourette?” in a French accent and I would respond with an enthusiastic “Oui” because where else would I be going? They’d then say something incomprehensible, but I understand the gesture – get in, and they’d drive me the rest of the way. That didn’t happen, and instead, I was left alone with my thoughts, contemplating my existence with each step up the mountain.

The Monastery

My first impression of La Tourette was disappointment. I had finally arrived, but I could hardly see it. In my mind, I had imagined standing in the field, much like I had seen in countless photos, with the monastery in front of me. Instead, the path takes you on a meandering journey so that you arrive from the back. It makes sense; it was built for monks who would live in it. It’s an outward facing connection with the landscape meant for those within, not for tourists. Later that evening, after a freak hailstorm, I’d make my way down through overgrown wet grass to sit by the pond and get the view I had hoped to see upon my arrival.

There’s no denying that La Tourette appears rough. It is Brutalist architecture after all, and as you arrive, you can’t fail to notice the rawness of the concrete. It sits there on the landscape, a grey monolith. You are encouraged to explore it. As long as a door isn’t locked, you can go in. I must have gotten there before anyone else because I didn’t come across another person until later. Unfortunately, it was a sunless day, like every day on my trip up to that point. The interplay of light and shadow, one of La Tourette’s most celebrated features, was nowhere to be found, but it didn’t cast a shadow on my mood and experience.

Exploring La Tourette was like walking through a living masterpiece, an extraordinary creation that unfolds with every step. The architecture and details speak, offering spaces that invite contemplation and surprise. As you wander through the monastery, the introduction of sun (which I did have for the briefest of moments!) transform even the simplest corner or surface. The concrete walls and floors become canvases for the sunlight and shadows. Each turn, each passage, each door, reveals something unexpected.

The Church

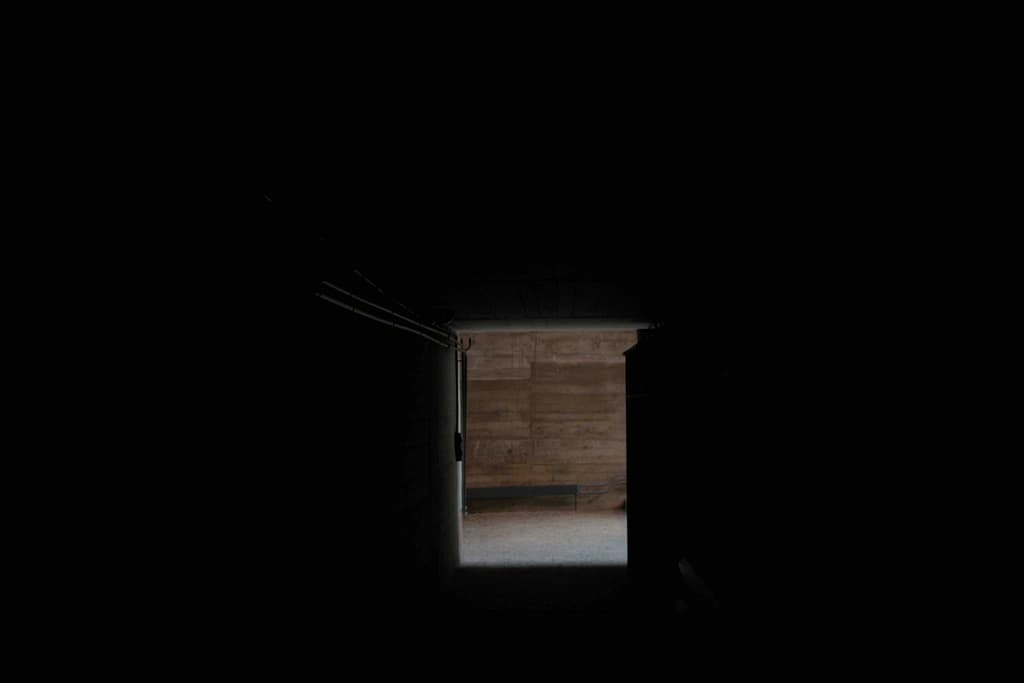

The Church is probably the most famous part of the monastery. It’s the giant concrete box. Inside, access to it begins with a decent along a slopping corridor, where the rhythm of your footsteps seems to harmonize with the irregular pattern of the window glazing on your right. I imagine, on a sunny day, light would filter in, casting a dance of shadows and reflections that feel alive with your own movement. As you reach the bottom, you’re met with a massive bronze door, with an oval-shaped opening reminiscent of a ship’s hatch. It offers just enough space to squeeze through, creating a moment of anticipation and tension before stepping in.

Inside, the space reveals itself as austere yet powerful. A cavernous concrete box. Light, though subtle, is deliberate – floating down from a squared skylight above, a large vertical opening at the rear, and gently coming in through the ribbon windows along the side. It is a space for quiet contemplation, where even the smallest of sounds echoes and reverberates, compelling you to speak in hushed tones or not to speak at all. The stillness almost dares you not to breathe, as if the very architecture and atmosphere demands silence and reflection.

Off to the side of the chapel is the entrance to the lower crypt. This requires keyed access from the receptionist. A short staircase leads you down. At the bottom, a dark tunnel leads to the lower crypt. Once through, you emerge into a room bathed in light. On one side, a concrete wall curves away, and on the other, seven white concrete altars ascend the sloping floor. Above it all, three colored circular skylights float like an extraterrestrial object. These can actually be viewed from inside the main church. The wall dividing these spaces isn’t a full wall and they are one of the first things you notice on the exterior as you approach the Monastery.

The Refectory

The Refectory is where all the meals are served for both visitors and monks. Breakfast was included with the fee to stay, which costs about €60 and dinner was an extra €20, which isn’t bad for the privilege of staying in one of the most iconic buildings of the 20th century. The refectory is in the front and looks out to the valley below. It was around that time I got to meet other architecture enthusiasts. I sat at a table with a Swiss couple, both architects and an Eastern European couple on their honeymoon who were on their own pilgrimage to see more of Le Corbusier’s work in France. I also met two undergrad students who had just graduated in architecture and their professor, along with his wife and son, as part of their postgraduate, grant-funded trip.

The dinner felt like a scene out of the movie The Menu, or Clue – a group of random strangers gathered together in this giant building with free rein, seated in a room for dinner. I expected there to be a murder at any moment, plunging the forty-or-so of us into an all-night murder mystery. That didn’t happen though, and I had some great conversations with the people at my table. It was nice to be among fellow architecture aficionados. After dinner, once everyone had arrived, we explored more, pausing to stand under the shelter of the entrance outside while it hailed. When it cleared up, just before sunset, I made my way down through over grown grass next to the pond to see La Tourette in its entirety.

The Cells

Each monk had their own cell. The cells were based of Le Corbusier’s idea of the modular man. They were 19’5” long, 6’ wide and 7’5” high. They all have a small balcony that allows contact to the outside and inside they have only what’s strictly necessary: a bed, a chair, a table, a wardrobe and a sink. They were small, but for me, it was heaven. It was my first time sleeping alone and not in a dormitory with several others in over a month. However, every sound in La Tourette is extremely amplified. The closing and opening of doors made clunking noises as people went to the bathroom and reverberated through the halls, making the building feel alive. The walls and ceiling of the cells have a weird popcorn-like texture that creates an odd, disorienting sensation as shadows were cast across them–it was like three-dimensional radio static.

The next morning, I joined the eight monks who still live there (they always have a few that rotate in and out), for prayer before breakfast. Afterward, I wandered around for one last time, revisited some viewpoints taking a few more photos. Then, I made my way back down the hill to the train station in L’Arblase, and boarded a train to Zurich.