Egypt is a land of dichotomies. A country whose contributions to modern society go unrivaled with architectural treasures and monuments that have captivated imaginations for centuries. But, to only talk about its monuments would do a disservice to the experience of traveling through the country. Modern Egypt seems to rely so heavily on the past that they seem to have forgotten the present, relying on a 5,000-year-old civilization and their achievements instead of fostering new ones.

The country’s long and complex history certainly plays a role in shaping its present, especially its history of colonization. I’m not downplaying the affect it has had on modern day Egpyt, but after only five days in the country (with five left), I was eager to leave it–a feeling I’ve rarely encountered in the 40 other countries I’ve visited. Every little interaction is a battle to not get taken advantage of. For those considering a visit, I would recommend booking a guided tour in advance to help with interactions and avoid unnecessary hassle.

Almost every interaction with the locals was centered around them extracting something from tourists. The relentless focus on tips or getting you to do something was disheartening and exhausting. Almost every person who approached did so with the intent to sell, solicit, or negotiate, often under the guise of friendliness.

Even the tourist police, who are theoretically responsible for ensuring the safety of visitors and the monuments, often behaved like unofficial guides or opportunistic beggars with guns. Given that part of their job description is to interact with tourists, it would be helpful if they were able to speak with them. In many cases they beg for tips, asking for it in exchange for providing access to restricted areas, usually a shabby rope strung between poles that can be easily circumvented. They act as informal guides that you didn’t ask for, often following you as you walk through, or for doing nothing at all.

An Incident

One such incident occurred with my New Zealand friend from the Aswan Hostel. After visiting Philae Temple, we decide to visit the unfinished obelisk in Aswan. The unfinished obelisk would have been the largest ancient obelisk, but it rests in the stone quarry, cracked where it’s remained for thousands of years.

It was low season in Egypt, so very few people were visiting during that time. It was just too hot. Aswan may be the hottest part of Egypt, reaching 112F by one o’clock. By 2pm, the quarry was deserted, the heat intense, 112F and we were the only people around. There was a guard booth on the granite hill above us, but it was too hard to tell from our position if it was occupied.

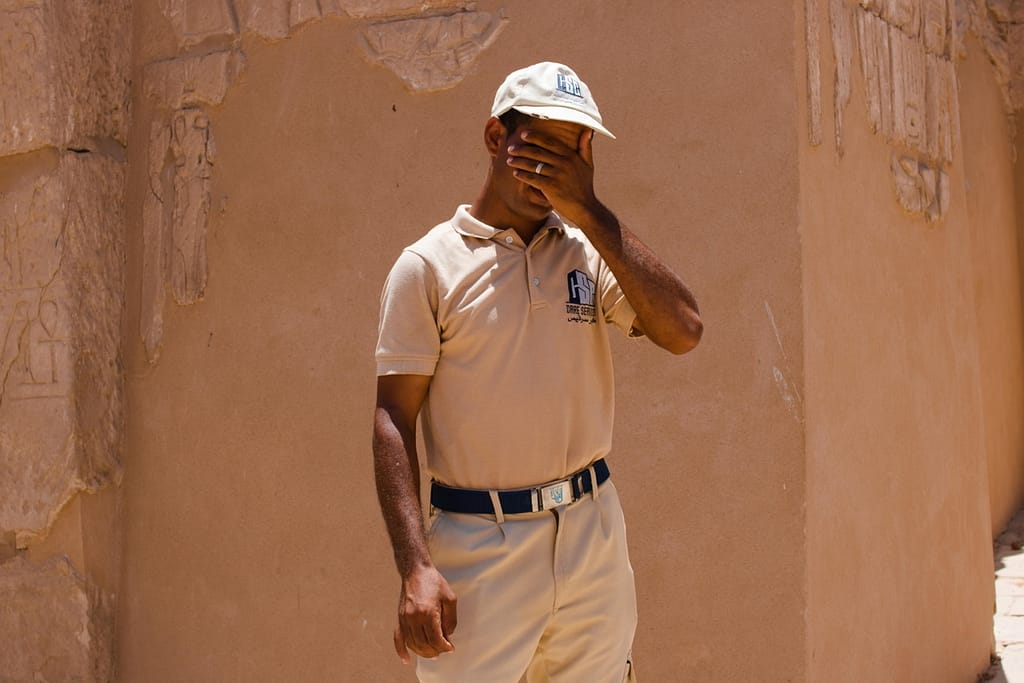

As we made our way around the obelisk, a cheery white uniformed tourist police appeared, seemingly out of nowhere. He walked toward us and gestured for us to follow him toward the base of the obelisk. He didn’t say much, just shushed us if we spoke, like we weren’t supposed to be there. We hadn’t even crossed any rope yet. Nobody was within eyesight and he was the police. Why the dramatics?

He beckoned us to follow him as he jumped onto the obelisk; he was adamant, so we did. He pointed to the carved granite ground on the side of the obelisk showing us that we could walk next to it. It was massive and towered above us. When we climbed out, he was waiting for something and made the universal money signal with his hands. My friend was already walking ahead up the granite hill and I point to him and mumble something like, “oh yeah, yeah.” When we got together, he stopped us and signaled again, making the same gesture with his hands.

Knowing my friend only had 20 Egyptian pounds ($.50) in his wallet, I asked him if he’s got this. When he went to give it to the police, he didn’t want it and instead said, “dollars”. My friend, a New Zealander, already made it clear where he was from, but in the eyes of the security guard, all tourists must have dollars. Instead, he beckoned us to follow him again. Begrudgingly we did because there was still more we wanted to explore, he had and gun and we needed to go that way, anyway. He showed us to another site, pointing at it like we wouldn’t have seen it if we were on our own. He then brought us to a temple who appeared out of nowhere, motioning for us to give the 20 pounds to him instead. I guess he wanted to keep his hands “clean.”

Temple Security Guards

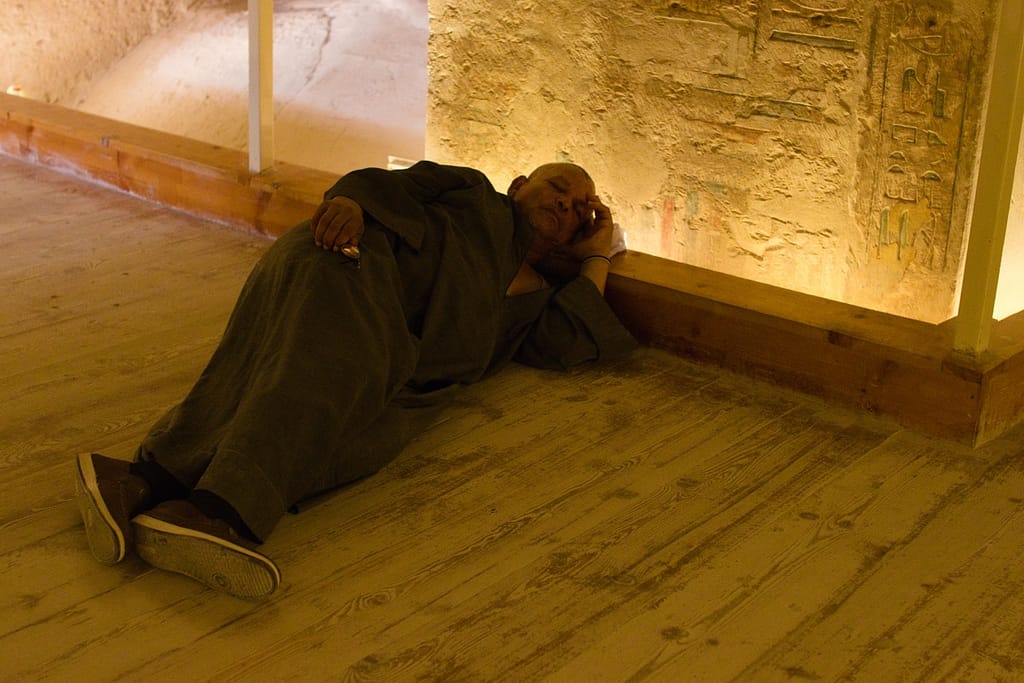

At every temple or historic site, you’ll encounter temple guards or security personnel. Sometimes there’s only one guard, while in bigger sites there may be a few. They are easy to spot, often right by the entrances so they can see their prey coming in, or they are roaming the grounds, hoping to corner tourists into giving them money. They are always men and wear traditional Egyptian galabeya. While it is technically illegal for them to take money, systemic corruption has made this quite common.

Like the policeman mentioned above, the temple guards are nothing more than a nuisance, beggars who turn an enjoyable experience into an unenjoyable one. As soon as you enter, they ask you, “where are you from?” a phrase used so frequently it is their default greeting. A harmless question uttered thousands of times. It is a way for them to gauge your nationality, which can influence their expectations for a tip, as certain nationalities are perceived to tip more generously. It also serves to pull you into a conversation, making it challenging to explore independently. I’ve found ignoring them often helps or giving a city in Egypt usually confuses them. Persistent guards, however, will keep rattling off countries hoping to guess the correct one.

Once engaged, they try to act as informal guides, offer information you didn’t ask for which usually comes in the form of pointing at a carving or hieroglyphic on the wall and saying one or two words in English. Some even offer to take you in “restricted” or closed off areas, which are usually sectioned off by a rope, closed doors, or simple metal barricade. I suspect that some of the restricted areas aren’t genuinely restricted, but rather made to appear that way for guards to profit by offering access. This behavior not only detracts from the experience but also risks undermining the preservation efforts of the monuments if visitors are brought into areas meant to be closed off.

Aswan and Luxor

While researching Egypt, you read about the constant harassment, but it leads you to believe that it is mainly confined to the area surrounding the great pyramids. I have found these encounters to be worse and more intense in other parts of the country, like in Aswan and Luxor. One key difference is that in many other countries, a firm “no” is usually enough to end the interaction, but in Egypt, people often continue following you, talking and attempting to engage long after you declined.

Exiting monuments requires passing through a bazar-like area filled with the identical souvenirs found throughout Egypt. Sometimes vendors cling to your arm as you attempt to leave. It may sound exaggerated, but until you are in Egypt and experience it, it’s hard to grasp just how constant this is. A friend I met who had solo-traveled across India mentioned that Egypt’s intensity was worse. In Egypt, “hello” is rarely just a friendly greeting. It’s often a precursor to something else.

In Luxor, I stayed on the quieter West Bank of the Nile, far separated from the chaotic-ness of the east bank. The east bank was like a mini Cairo. To reach town, it is about a 30- minute walk through the village, flooded fields and banana trees. Every single person I passed along the way either tried to sell me something or offered a service.

I was exhausted from this constant harassment. I thought recording the interaction would limit the interaction. It didn’t and the video below is the result.

First, I passed a tuk tuk filled with animal feed with two kids sitting on top, a couple of boys standing next to them and one in the street holding a mango. As I walked past, the one holding the mango immediately tried to sell it to me. Two minutes later I turned the corner and a guy came out of his house, warmly saying “Welcome my friend!” “How are you?” As I continued walking, he continued, “First time here? Have I seen you before” pacing behind me as I continued walking, now asking me if I wanted a sunset boat ride, a car or whatever else he could think to offer. Moments later, a man on a motorcycle appeared from the banana fields on a motorcycle, as if conjured by a magician. He didn’t even look at me as he turned left, but he stopped just ahead and as I walked past, asked if I wanted a sunset boat ride, or to rent a motorcycle. No more than two minutes later a kid, a young kid and his mom were sitting by the road, a boy–no older than 14 jumped up from the roadside, eagerly saying “hello, my friend, do you want to go on a boat ride?”

No, I didn’t want to go on a boat ride.

As I continued walking, I got a few more offers for boat rides, even though the sun had already set. Some asked if I wanted to cross to the other side. One man lied about the distance to the ferry (I wasn’t crossing), claiming it was far away, despite it being just a two-minute walk away. Slightly further ahead, a young guy sitting on a railing jumped up as he saw me and asked where I wanted to go and if I needed a ride to any of the temples. Twenty seconds later, I passed a trio of young men who asked if I needed a boat. There is no way to avoid the constant harassment. If you ignore them, they keep talking. If you talk back, they act surprised when you’re annoyed. If you answer no, then they know you understood them. It seems like they don’t understand that if you treat people fairly and with honesty, then people would be far more willing to pay for their services and even tip generously.

In the short video below, I was minding my own business, walking back to the hotel and recording the landscape as I walked to catch the call to prayer as it rang out.

Moments of Genuineness

That said, there were moments of genuineness, such as with two taxi drivers in Luxor. The first one was a young man who exuded happiness. He was eager to practice English; he didn’t try to overcharge us, and came across as a genuinely kind person. I regret not tipping him more, or getting his number so that we could drive with him again. The wages of taxi drivers are pitifully low in Egypt. Egypt is an increasingly expensive place for locals, so while I understand the hustle, I don’t agree with their tactics.

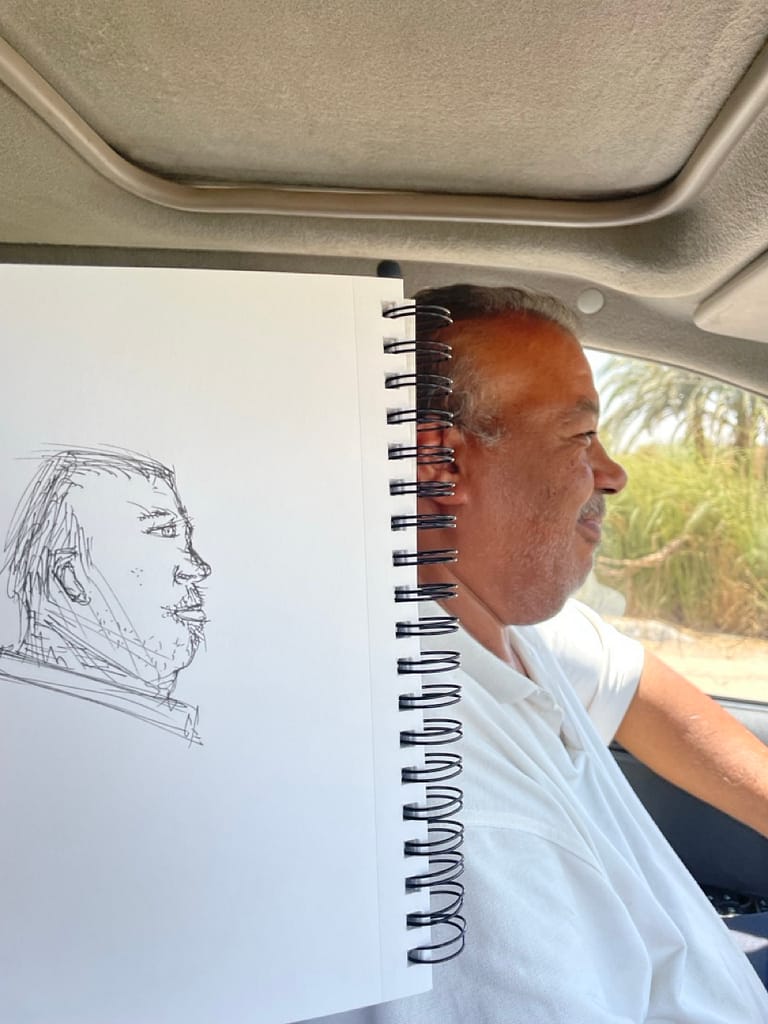

The second taxi driver picked us up from Karnak temple to take us to Luxor temple. During the short ride, he asked about our plans. My friend was leaving the next day, but I wanted to see one last temple the following day, my last in Luxor. When I asked him how much he would charge, his price was half of what my hotel had quoted, so I agreed to go with him.

The drive to the temple was about an hour and fifteen minutes each way and we communicated in a mix of broken English and gestures the whole way. When we arrived back to Luxor, I was more than happy to give him more than the agreed upon price because I was already saving money from what I would have paid. I also asked if he could drive me to the airport the next day and he gladly accepted. For a taxi driver, landing a tourist who needs multiple rides is like winning the lottery. We were the same age and he had just had his third child, a baby girl. After he dropped me off at the airport, I gave him twice the amount he asked for, the last of my Egyptian dollars. He texted me not long after thanking me. It was one of the more meaningful interactions I had in Egypt.

Genuine or Not?

In Cairo, I did two days of tours with a friend’s dad who is a tour guide and Egyptologist. After two days with him, I trusted him to some extent and I asked if he knew anyone in Luxor who could take me around and guide me for four days. He said he knew someone and would talk to them. Later, he told me it would cost $300, which included being driven from Aswan to Luxor–a four-hour drive with stops at three temples along the way, two days of touring in Luxor and a day to a temple outside of Luxor. At the time, $75 dollars a day seemed like a fair price, especially after the two-day Cairo tour, cost me $200 (plus $60 in tips for him and his son who drove). However, I soon realized the individual costs.

While in Aswan, I learned the hostel was offering rides to Luxor for $60 and I met an English couple who paid $82 for theirs. Also, I realized the two temples on the east bank of Luxor are within walking distance of each other, so I didn’t need someone to drive me around. My hotel in Luxor quoted me $80 to have someone just drive me round for three full days, no guides. I didn’t want any more tours; I preferred to explore the temples at my own pace.

When I contacted the Cairo guide’s referral to cancel the tours and asked for a price just for the drive from Aswan to Luxor, he told me $100. Armed with information, I countered, saying, “no, that’s way too high.” He came down to $90, but without entrance fees (so still $100). I negotiated down to $75. I felt somewhat obligated since we had been discussing the tours and he and I had the connection with the Cairo guide.

On the morning of the trip, he didn’t even come to pick me up. Apparently, his son was sick, so he sent his uncle. I only found this out when the uncle (who I thought was him) handed me the phone to speak to him. During the drive, the uncle turned out to be a great guy. He told me he received very little of the overall fee and relied mostly on tips. Whether it was true, or if he was telling me to get a bigger tip, I don’t know.

Once I arrived at my hotel in Luxor, I spoke to the owner of the hotel, who was one of the most trustworthy people I met in Egypt. I realized I didn’t trust the guide or the prior arrangement we had anymore. I decided to cancel. When I spoke to him on the phone, he asked me if I tipped his uncle well and wanted to know the amount (the hotel owner was shocked when I told him about this). I said that it was none of his business and he could ask his uncle directly. The guide then told me that how much I tipped depends on how much he pays his uncle. If it was large, he’d pay him less (so maybe there was some truth to what the uncle said).

Canceling the tours was the right decision, but the experience left me retroactively questioning the Cairo guide’s trustworthiness, as he had set up the arrangement. It also had me questioning the validity of what he said during the tours.

Corrupt Police

Lastly, there’s the police. The police in Egypt are like an organized group of extortionists, creating roadblocks and checkpoints, forcing drivers to give them money. Apparently, some roads are off-limits to tourists, but a small bribe to the officer can make that restriction disappear. I encountered this on multiple occasions with my drivers.

The first instance happened with the uncle. At the checkpoint, I don’t think he actually gave the officer any cash, but instead said that I was hungry and angry and that we were going to get some food and that we’d only be ten minutes. I don’t know if that’s what he actually said, but I also didn’t see him hand any money over.

The second time was a series of instances with the taxi driver on my last day in Luxor. At the first checkpoint, he tried to give the officer, who came to the car window 20 Egyptian ponds (less than 50 U.S. cents), but it wasn’t enough. He made him get out of the car and go to the police vehicle, where they demanded 100 Egyptian pounds ($2). Later, after leaving the temple, the police stopped us just outside of the parking lot. This time, the driver offered another 20 pounds, but the police kept pulling out more until he was satisfied with 50 pounds ($1). To avoid further checkpoints, the driver took us off the main road; we crossed a narrow bridge as wide as the car and navigated down a dirt path. We passed wandering chickens, poorly constructed houses and children along the road. It was the only time in Egypt I actually felt scared for my safety. I really thought there was a possibility the driver was going to extort more money out of me.

Later on the highway, we encountered a third checkpoint. Afterwards, I asked what had happened because the police officer walked away looking dejected. He explained that he told the police that he already had to pay 100 pounds at one stop and 50 pounds at another and if paid anymore, he’d have no money. I asked what would have happened if he didn’t let us go, and he said the police was a lower rank. If it was a higher rank, he would have been a lot more aggressive and he would have had to pay more.

The video below is from the first checkpoint when he was asked to leave the car.

No Drones

One final story. My Aswan friend Aswan and Luxor (from the unfinished obelisk story) entered Egypt on June 19th with a drone, unaware that drones are not permitted in the country. After spending seven hours at border control or customs, he finally was forced to relinquish it. He was charged a small fee and was given a piece of paper indicating they had his drone, and was assured that he would be able to retrieve it upon leaving.

He left Egypt on June 29th without his drone.

On June 28th, the day before his departure, he went to the airport to verify the procedure for getting back his drone and to ensure he knew where to go. The staff assured him that he would be able to get it on the day of his flight. The day of his flight, he arrived hours early to the airport, and nobody was willing to help him get his drone sorted. He even speaks Arabic, so communication wasn’t the problem. The staff repeatedly insisted the drone was in terminal 1 and since he was in terminal 3, he couldn’t get it. He had done everything they have asked for and they kept talking to him in circles.

To make matters worse, the officials claimed he never entered the country legally and that he didn’t have the correct visa. They then tried to extort him for money to clear passport control. He didn’t pay, but instead gave the money he was going to use to get back his drone to a cleaning staff nearby.

In the end, he left Egypt without his drone and bitter reminder of the inefficiency and corruption he had encountered while in Egypt. Something that unfortunately all tourists encounter while visiting the country.

Experiencing Egypt Part I: A Journey Through The Pyramids

Experiencing Egypt Part II: Aswan & Luxor

Experiencing Egypt Part II: An Exhausting Experience

Pingback: Experiencing Egypt Part I: A Journey Through the Pyramids - JourneymanJoe