Concrete is the only material available without an inherent form. It’s the architect’s dream material, making it capable of taking the shape and modulations imposed upon it. Its expressiveness, fluidity, and dynamism are only some reasons it’s continued to be used today. Casting with concrete is a complex process that requires a profound comprehension of the material’s properties.

History of Concrete

Its roots can be traced back to the ancient Romans, who accidentally discovered a silica and aluminum-bearing mineral on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, that when mixed with limestone and burned, produced a cement that exhibited a unique quality. This material, when mixed with water and sand, produced a mortar that could be hardened underwater as well as in the air. Knowledge of this type of construction was lost with the fall of stone and not regained until the end of the 18th century. Around the 1850s reinforced concrete, where steel bars are embedded (giving it its structural quality) was invented.

An architect must know the materials they are using. It’s important that they learn how materials feel in the hand, how they look in a building, how they are manufactured or created, how they are put into place and how they perform and age with time. The physical properties of the materials is one of the drivers of design and the creators of form. For our materials and construction class, we had to do a material study project. I chose to use concrete and to make concrete breeze blocks. A breeze block is a patterned block, used as a screen or shading device, that allows the wind through.

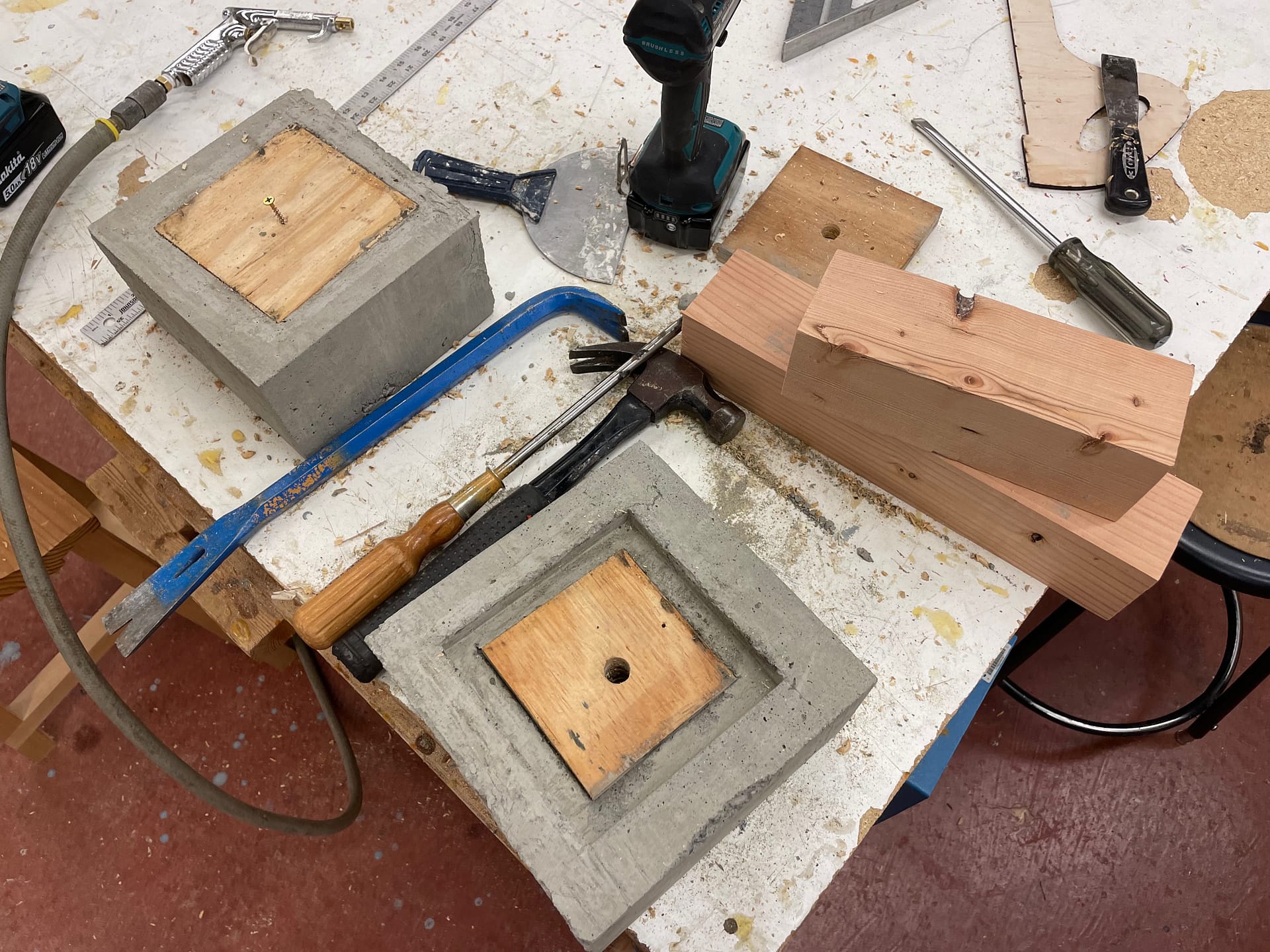

Working with concrete was not easy. There was so much I needed to figure out and if it wasn’t for my friend Patrick I don’t think I would have. First, I had to design the block. Then I had to figure out the formwork that will allow me to create the block. The design can easily be influenced by the limitations of the formwork. Lastly, there’s making the formwork, getting the correct concrete, mixing the concrete, pouring it, letting it cure “dry”, and ultimately taking the formwork off.

The Process

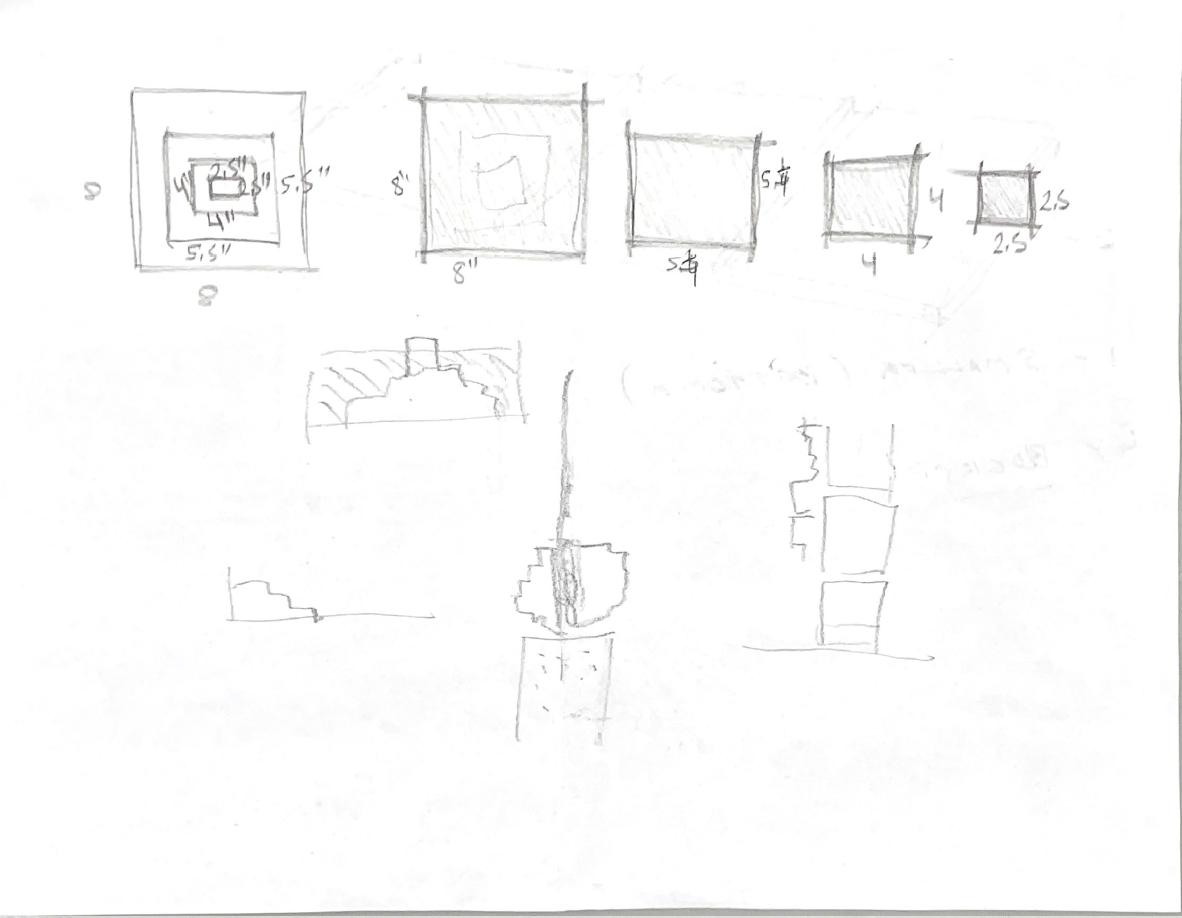

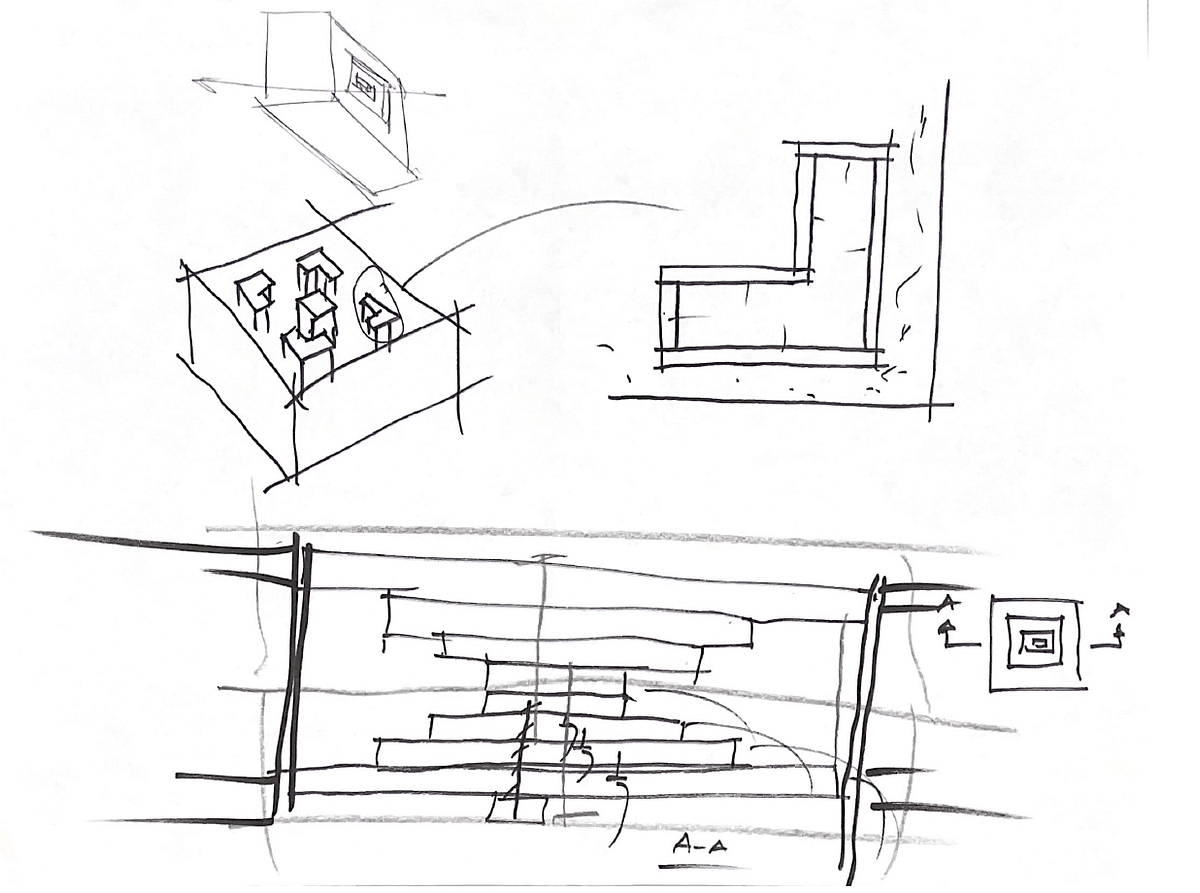

My initial sketches were based on mid-century modern breeze blocks. However, after talking to my friend, I quickly realized that they would be extremely difficult to cast. He helped me come up with a new design that was meant to make it easier to take the formwork off once the concrete cured.

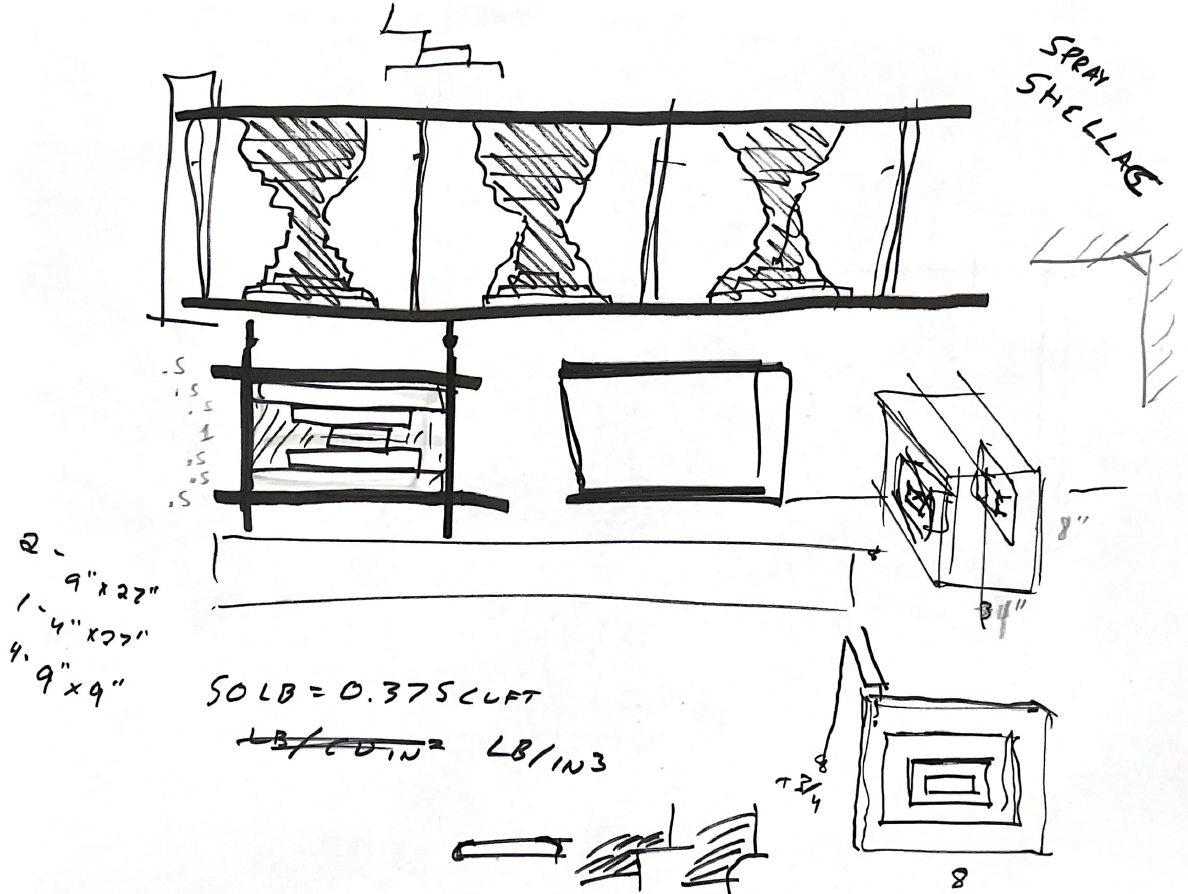

Obtaining concrete proved to be a unique challenge. I probably spent an hour and a half at Home Depot, primarily staring at the various bags of quikrete. Quikrete is a brand that combines the elements of concrete in an easy to purchase 50-80 pound bag, however there’s like 5-10 different types. It makes it really confusing to know which one you’ll need. It sets fast and is cheap, a 50 pound bag costs around $8. In addition to the concrete, reinforcing like chicken wire is needed to strengthen the concrete, gloves because concrete can cause severe burns, buckets to mix the concrete, and the wood to make the formwork.

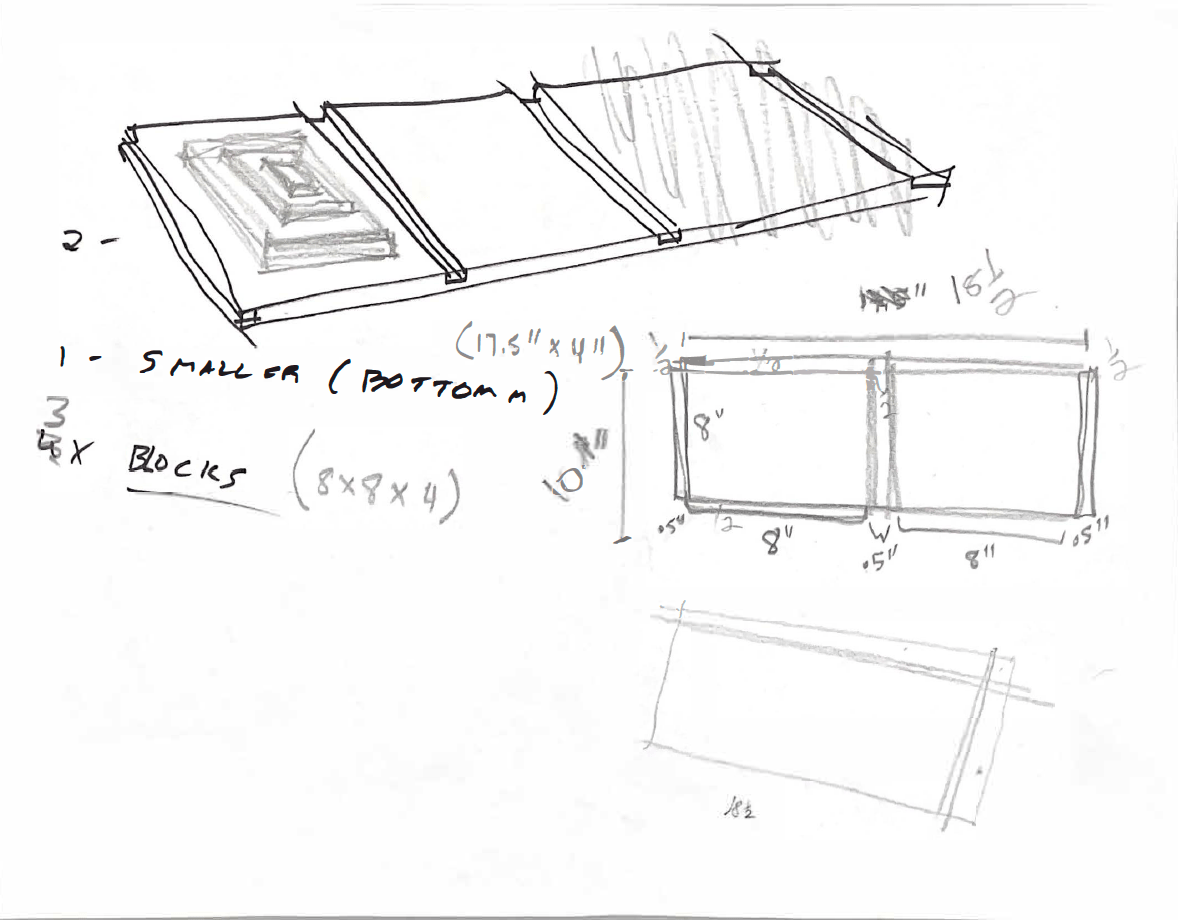

Making the formwork was difficult and required significant help in the wood shop from the two instructors there. Without their guidance and help, there’s no way I could have done it.

Casting with Concrete

Pouring the concrete started off well. I had two blocks to pour and figured I would use half the bag and half the amount of water to start. However, as I was mixing it, I noticed I couldn’t get the bottom. It was almost like trying to mix water into flour. I was getting nervous that it was drying, so I poured into my mold only to have it get stuck and sit atop on my chicken wire reinforcement. I panicked and pulled it out and continued pouring the concrete. I didn’t know what would happen because with the reinforcement, concrete could easily crack when taking off the formwork. Also, concrete needs to be vibrated while it’s setting to get the air bubbles out. Air bubbles can weaken the concrete. I didn’t have a concrete vibrator, so I shook the mold for a bit. I had no idea what I was doing, or if it was doing anything.

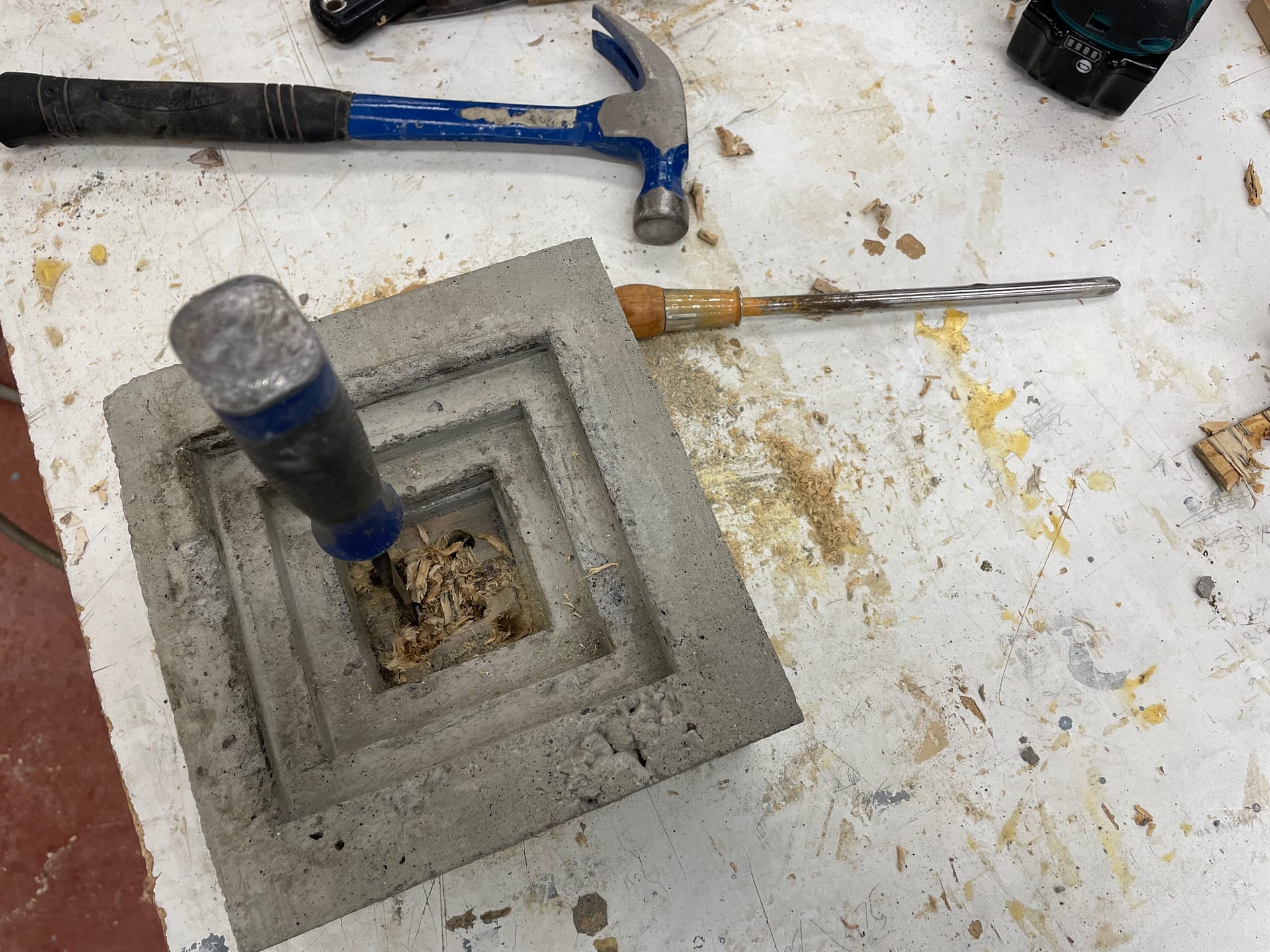

Taking off the formwork was so incredibly difficult, I almost wasn’t going to do it for the second block. I used every tool available in the wood shop for two hours straight, and that was only for one block. At moments, it seemed like no progress was being made, but slowly and through sheer force and determination, I removed the wood. They’re not pretty, but they’re handcrafted cement breeze blocks. I have such a profound respect for buildings that are made of concrete and for those doing the work.

WOW LOTTA WORK, but job well done!!!

It really was! I’d like to try using it again, but making something that can come out nicer

Pingback: A Year and a Half Gone, A Year and a Half to Go – Journeyman Joe