This book gives an eye-opening account of the role architecture and the built environment have played in Syria as well as showing what some people have to go through to survive. At the time of the book, the author Marwa Al-Sabouni is a young architect living in Homs, Syria during its civil war in the mid-2000s.

The war in Syria is still ongoing and has killed at least 350,000 and displaced millions more. Homs, is the home of the author and where the war began. It’s where the first anti-government protests erupted in mid-March 2011 and was sieged for three years by government forces until 2014. Thousands of civilians lost their lives. Marwa Al-Sabouni mentions the war as a machine, “you descend one terrifying slope to find yourself immediately ascending the next.” She recounts the first day the deadly mortar strike was introduced to her, “the shouts and giggles of children at play were coming through my window… we heard a heavy landing, as if a giant bowling ball had landed next door…I looked out and saw the children- I saw them all lying dead.” How do you continue to live when you are faced with that daily? Around the world people are going through similar experiences like this. How do you move toward a hopeful future after the distraction man enacts on his fellow man? What role can architecture play in healing?

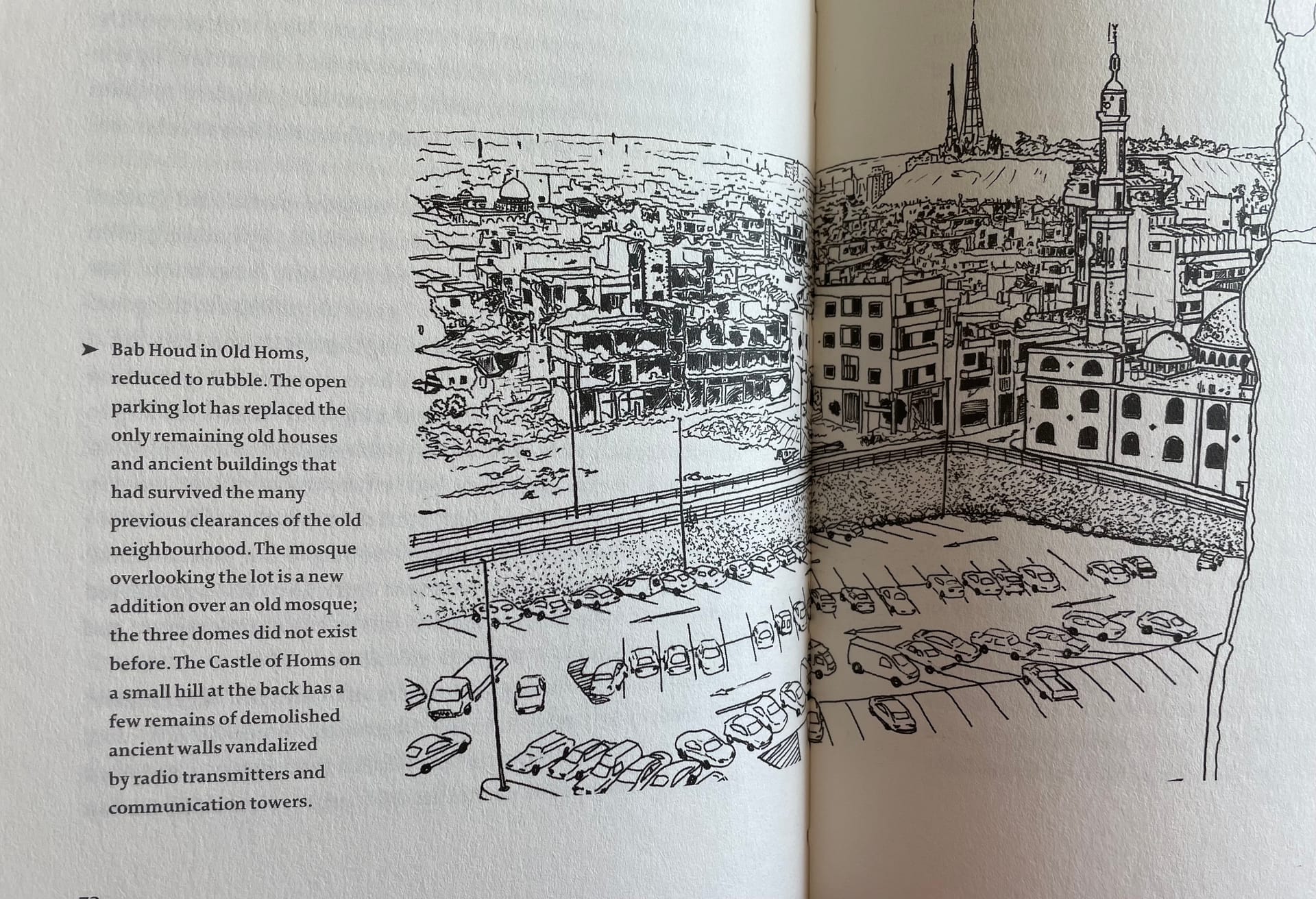

In this book, she examines the role the built environment and architecture played in creating, directing, and heightening conflicts between warring factions. She argues that there is a resemblance between the architects of a place and the character of the communities. She says, “Our architecture tells the story of who we are.” Syrian communities had a shared approach to life before the war, tolerating freedom of belief, and accepting other ways of life. However, starting in the 1950s, a petrol factory, a composting factory and a sugar factory were built on the west side, the side in which the winds come from, blowing pollution and an unpleasant smell. Also, in the 1950s, the government issued an Expropriation law that allowed them to confiscate private property for public use. “They built parking lots where markets previously existed, corrupt politicians collaborated controlling the built environment, not for betterment, but for profit, reducing a city with a defined character, instead to a city of “mood-anism.” The forms of the building are dictated by the mood of the rulers. She mentions an example where a former mayor diverted a main road to save her house from the noise and renovating the street furnishing around her home, an area of exclusive villas for the wealthy. Various housing commissions have been put into place, creating clusters of raw buildings that popped up in isolated locations, fraud and corruption preventing a chance for actual change. She refers to an architect in such a market as a “ghost architect.” They have no role in creating visions or suggesting improvements. Is it possible for this to change with a change of those who are in power? A city being used like a monopoly board makes it difficult for those who are living it to feel a sense of identity to it.

“How can an architect create Home in any building when he himself has never experienced it? When all that he has seen around him is a trampled life that seeks relentlessly to emerge. Home is the goal of architecture, and true home is like a mirror that always shows us our best profile, no matter the relation we stand to it. But when a building shows only our worst side, and when it is the wreckage of our dreams, then it is no longer a home, and nor is it architecture.”

Architecture isn’t the only factor; it would be presumptuous to assume so. However, architecture can play an important role in healing. For Marwa Al-Sabouni, Syria, for Homs, healing cannot come from “merely replacing our informal slums with faceless towers.” She says, “our need is a shared home, and this home must be ours, built from our sense of who we are as citizens of this place, and from our wish to restore it, to embellish it, to make it our own, and to hand it on as a gift.”

These are my favorite lines/quotes from the book:

“the failure to create architecture that can constitute a home for its users stems form a loss of identity, which in turn has causes that go deep into the psychology of our people.”

“there is an inescapable correspondence between the architecture of a place and the characteristic of the community that has settled there. Our architecture tells the story of who we are.”

“in the face of human suffering and pain, architecture tends to dissolve.”

“our homes don’t just contain our life earnings, they contain our memories and dreams; they stand for what we are. To destroy one’s home should be taken as an equal crime to destroying one’s sou… questions that puzzle any architect who wishes to do something: where to start, how to heal, how to avoid being trapped in a vicious cycle of bad choices, how to respect rights, how to et away from division, how to reunite shattered parts, what to preserve and what to let go, what lessons to take and how to guarantee their application?”

“the building of concrete blocks lacking the least aesthetic sense or architectural vision denies the city its character and deprives its citizens of a congenial environment.”

“in Syria people haven’t just lost a part of their identity; they have lost most of their built history and all of their present… identity in all its forms depends on continuity and memory, and architecture is the main publicly recognizable register of that… registered continuity and collective memory are most visible through architecture.”

“modern architects seems to feel obliged to sell their product as having some special connection with history generally, and with the history of the place they are about to desecrate specifically.”

“architects know that they out to achieve identity with the place they are building. Identity cannot be achieved as a prescribed recipe. It is not an independent goal of design, but a by-product of designing meaningfully and beautifully, according to the spirit of the place.”

“what determines the right architectural experience, and how can it have meaning and be judged?”

“as an architect or designer I can ask myself questions such as: why do I need this ‘door’? What is the function (in the wide sense of the word) of a door?”

“stereotyping burdens architecture with an imposed message that denies its inner vitality.”

“you don’t build for the Middle East by designing important gargantuan structures and Corbusian plans, and then encrusting the result with ‘Islamic’ icons. You build by making a livable home for both rich and poor, Muslim and Christian, owner and tenant, adult and child, in which parts, localities, functions and businesses are woven together in a continuous fabric, and in which a shared moral order emerges of its own accord.”