I recently stumbled upon a thought-provoking blog post that resonated with my own reflections on the principles of Post-War Reconstruction and inspired me to write a similar piece. The blog was written by Lebbeus Woods and it is titled, “War and Architecture.”

Who is Lebbeus Woods?

Lebbeus Woods was an American architect, “known for his fantastical drawings, imagined deconstructed buildings, and dystopian landscapes that relate as closely to science fiction as to architecture. ” (quote from dezeen). He co-founded the Research Institute for Experimental Architecture, which focused on finding architectural answers to contemporary world problems. He also has a series of drawings and writings devoted to war and architecture, which also is the focal point of his book bearing the same title. This exploration was ignited by the bombing of Sarajevo in 1992.

Woods outlined two principles that emerged from his research into post-WW2 reconstruction.

The Principles

1.Restore what has been lost to pre-war condition. The idea is to erase the effects of war and return to a form of “normalcy.” To imagine the city, not as a place ravaged by war, but rather as what once was. We can see this in cities such as Warsaw (although technically it wasn’t restored as it was, but a reimagined version of the city based on paintings done by Bellotto), Bruges, and Dresden.

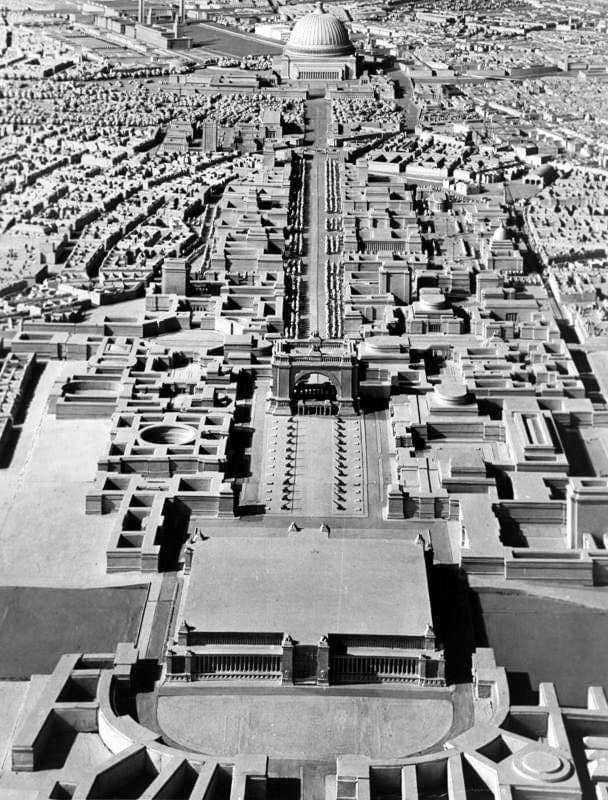

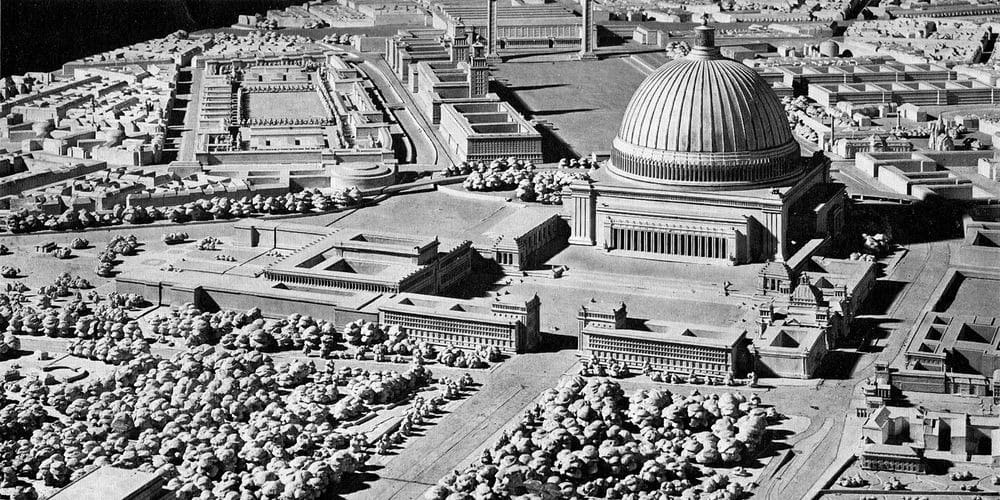

2.Demolish the Damaged and destroyed buildings and build something entirely new. According to Lebbeus, the new could either be radically different from its predecessor, or an updated version of the pre-war norm.

The first two principles reflect is the desire of most city inhabitants to get back to normal and forget the traumas they experienced. They also erase the memory of war from the built environment and the people who experienced it. According to Lebbeus, “The pre-war normal no longer exists, having been irrevocably destroyed, Still, this does not mean that many—even most—people will not desire to do so. In such a society, wise leaders are needed to persuade people that something new must be created—a new normal that modifies or in some ways replaces the lost one, and further, that it can only be created with their consent and creative participation.” For him, this calls for the emergence of a new reconstruction principle.

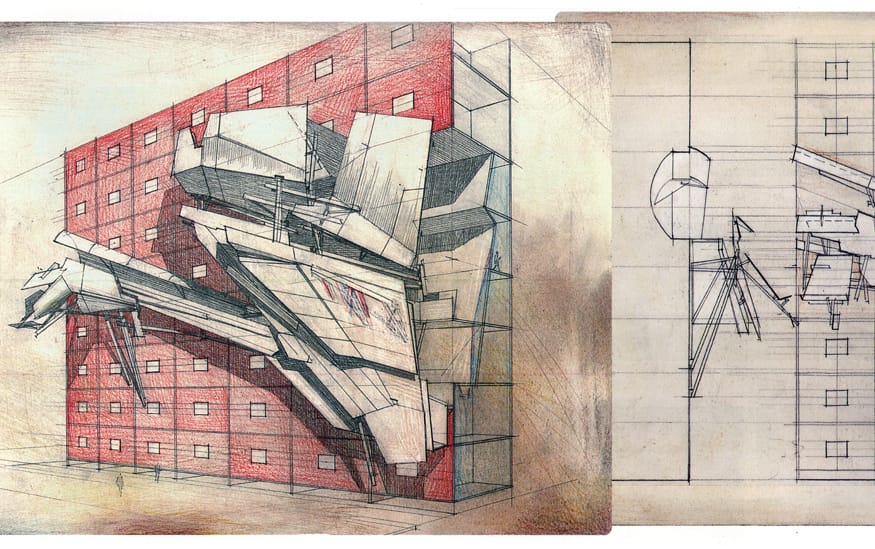

3.The post-war city must create the new from the damaged old. The ordinary buildings, offices, apartments, etc., should be transformed from the familiar old to the unfamiliar new. “Symbolic structures, such as churches, synagogues, mosques and those buildings of historical significance that are key to the cultural memory of the city and its people, must also be salvaged and repaired.”

During my research, I realized there might be a crucial, albeit often overlooked, fourth principle that really exists between the second and third. It’s not a new principle of reconstruction, but rather one that was used post-WWII, although in much rarer instances and only with a select few buildings.

4.Leave the demolished building as is in its ruined state. In rare instances, rebuilding doesn’t conform to the first two principles, but instead, the destroyed building is preserved in its devastated state, serving as the sole reminder amidst a city’s reconstruction. Such is the case with the Genbaku Dome in Hiroshima, or the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, in Berlin.

In the endeavor to rebuild a city, I believe that all four of these principles should be considered. The collective memory of a place is as susceptible to destruction as its physical structures. Thus, it is important for the inhabitants to feel some sense of familiarity with the rebuilt city. This underscores the importance of restoring what has been lost to its pre-war condition. However, that doesn’t mean its pre-war condition can’t be modified, as exemplified by the Reichstag in Berlin. In 1955, it was rebuilt without its dome due to structural concerns. In the late 90s, Norman Foster spearheaded further renovations, introducing a space for the new parliament and a modernized glass dome where German citizens can look down on their legislators. A symbol for the new unified Germany.

Perhaps symbolic interventions like those witnessed in the Reichstag are integral to a city’s healing process. The blending of the new with the familiar, and the new from the damaged old could help facilitate recovery and renewal.

quotes are from his blog unless otherwise noted – Lebbeus Woods blog

Warsaw photos are from – birdinflight.com

Very interesting JoJo!!!