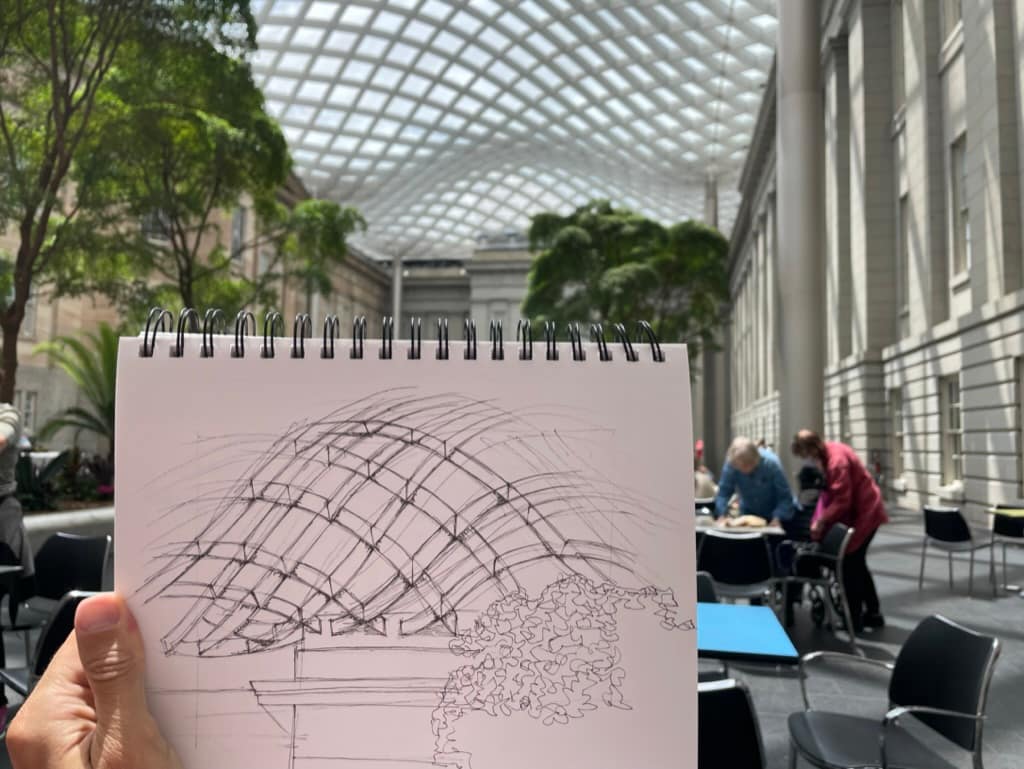

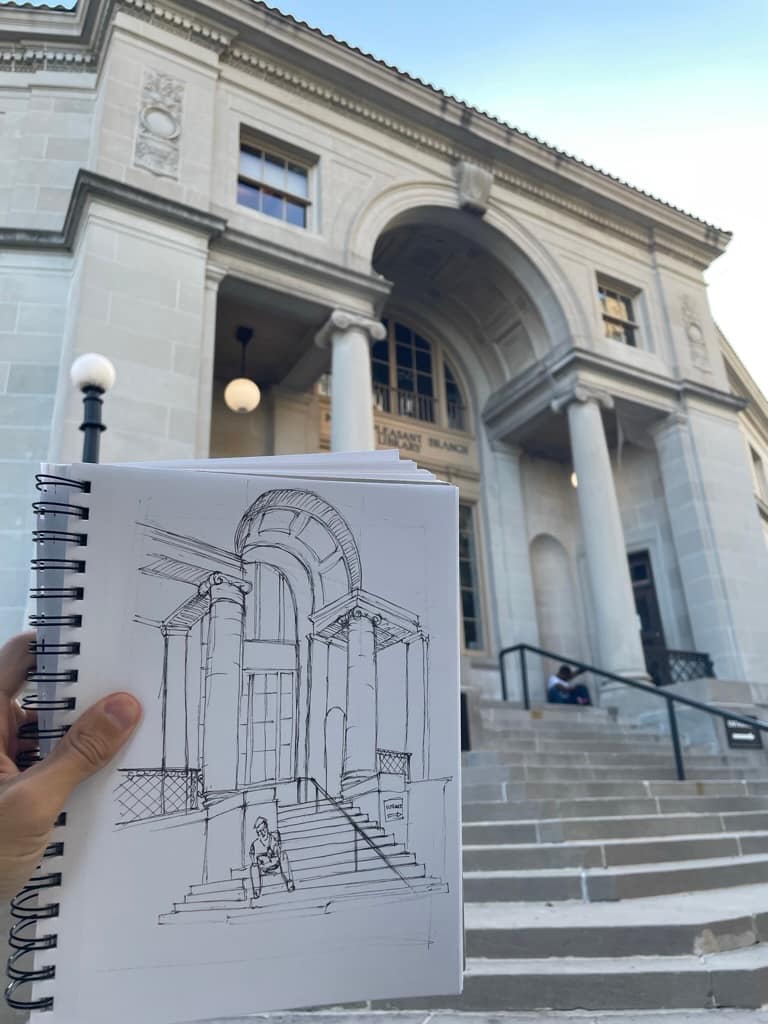

At the beginning of the summer, I set a goal to sketch every day that I was in DC. It wasn’t for graduate school, or for any particular class, nor was it a requirement for my internship, but rather something I wanted to do. We’ve been told that as an architect when you travel, you should sketch. Not only does it help you intimately know a building or a place, but it also helps to maintain the connection between the eye and the hand. Sketching is the way in which architectural ideas are realized. Every great building started with a sketch.

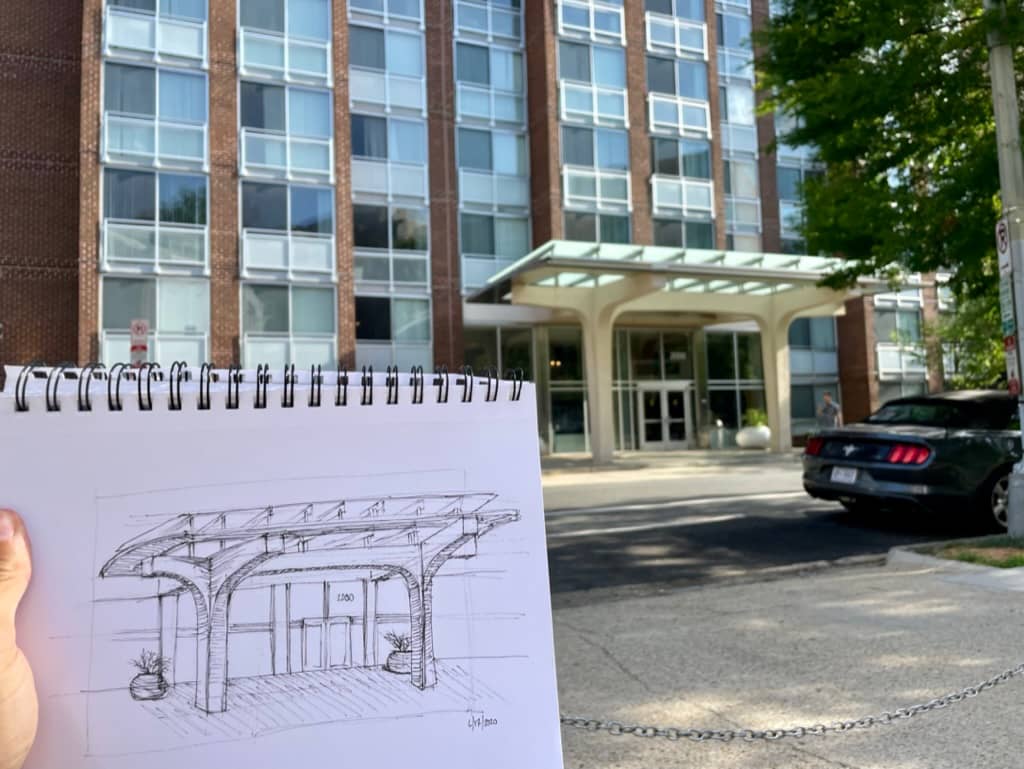

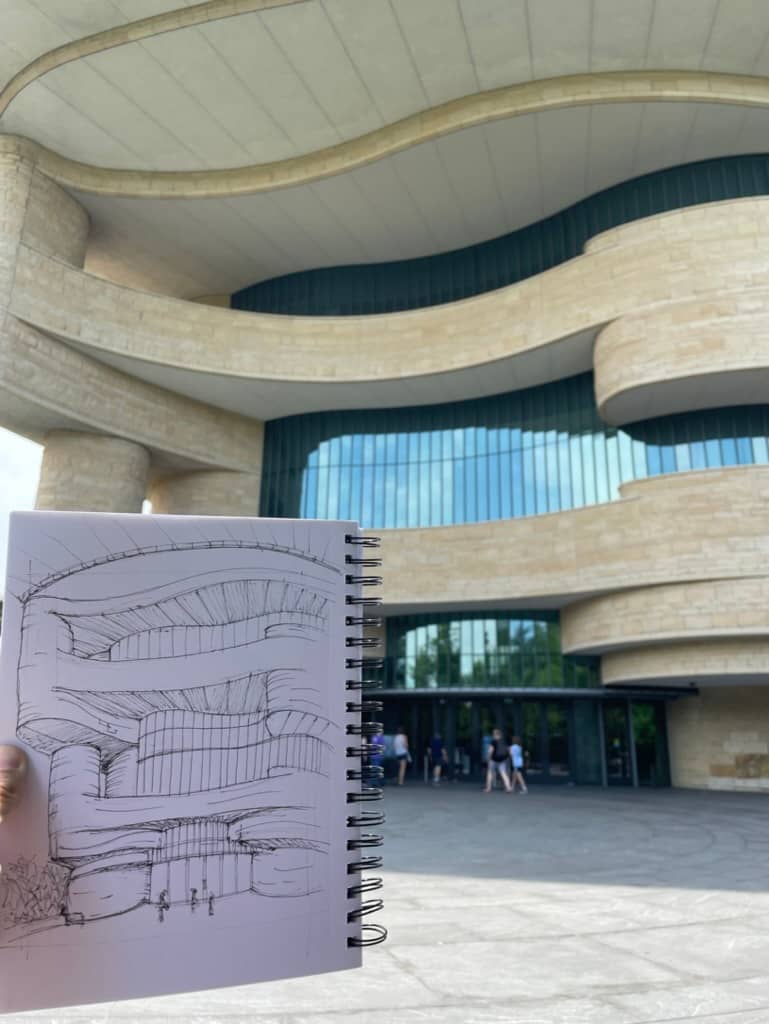

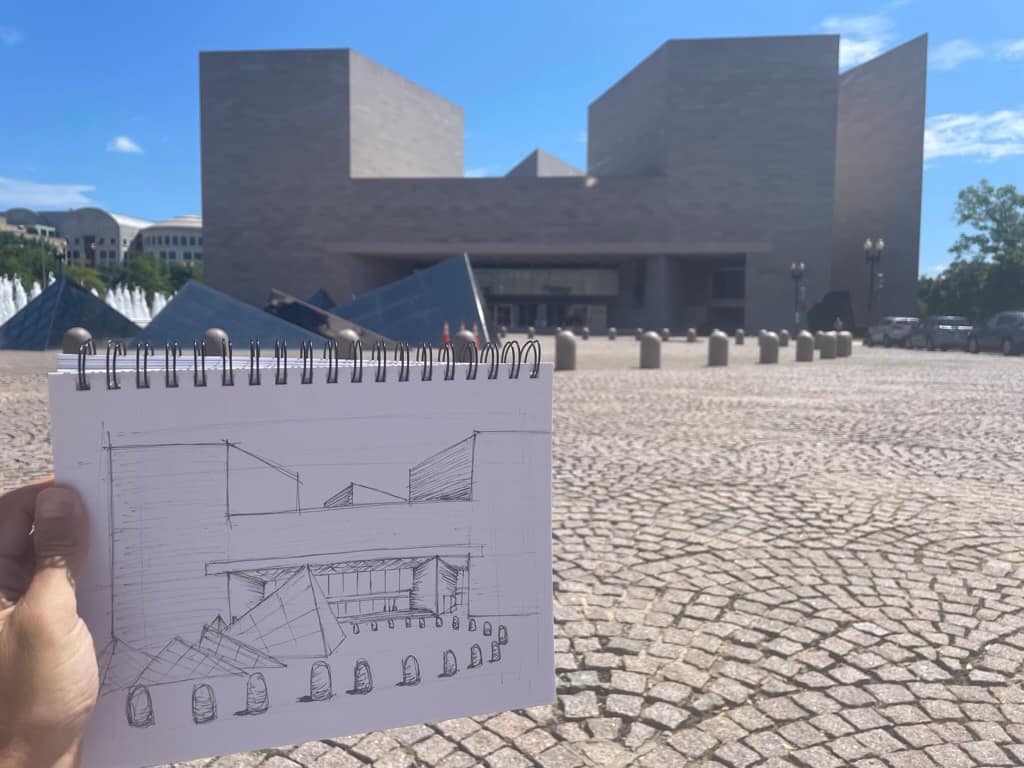

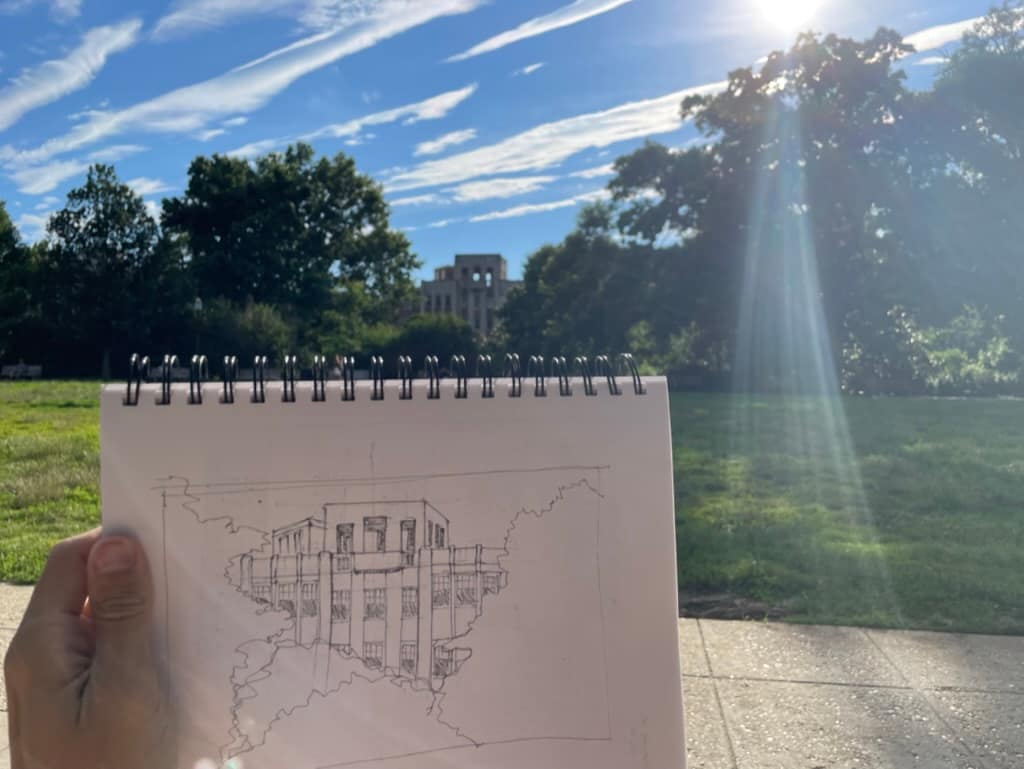

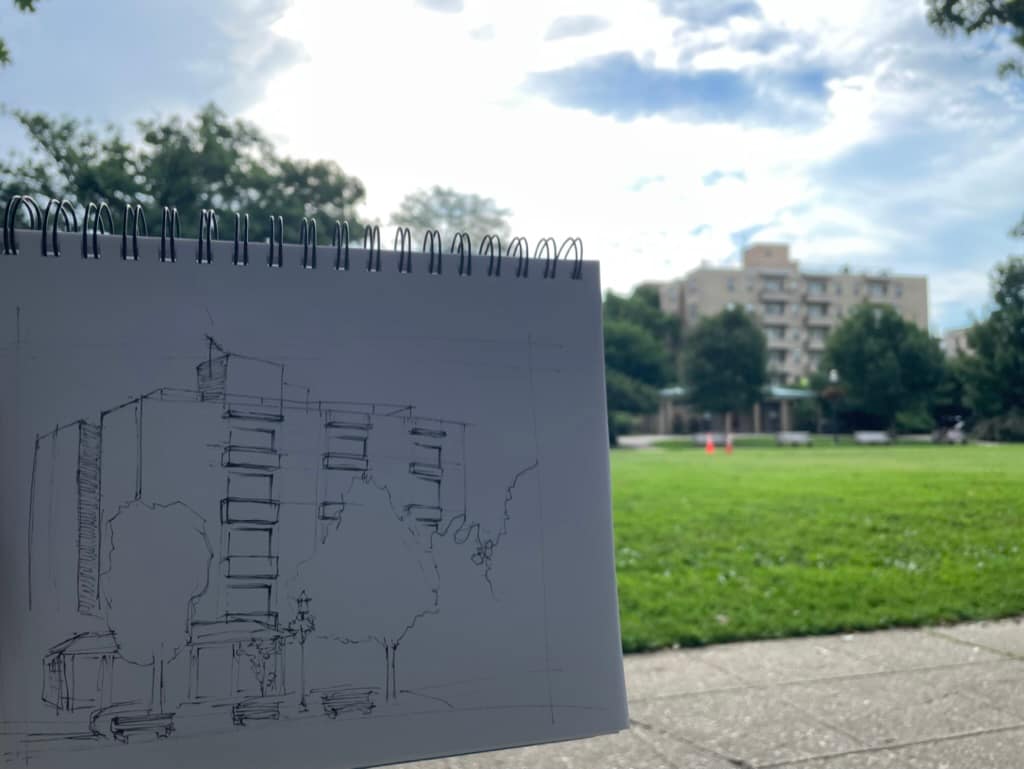

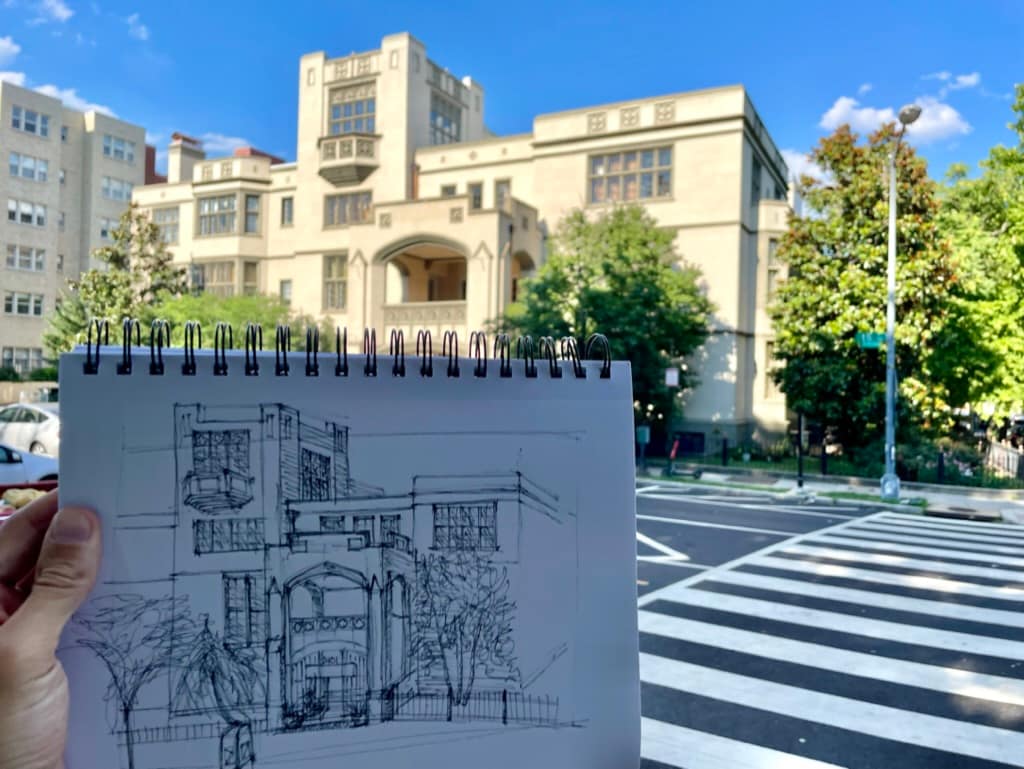

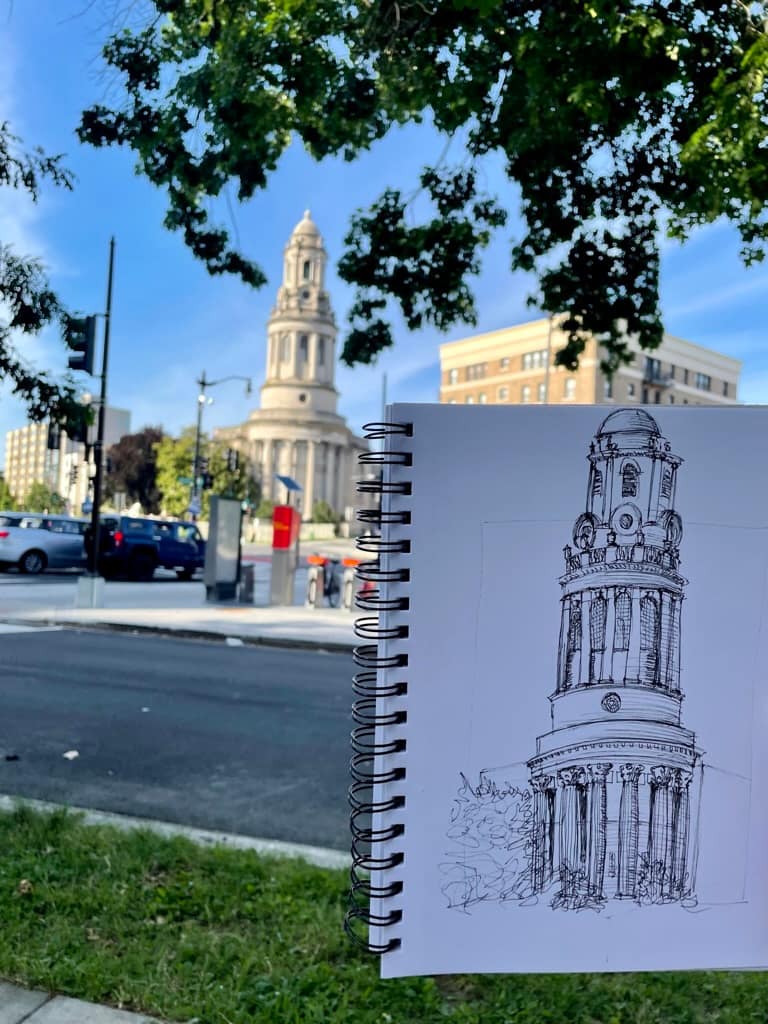

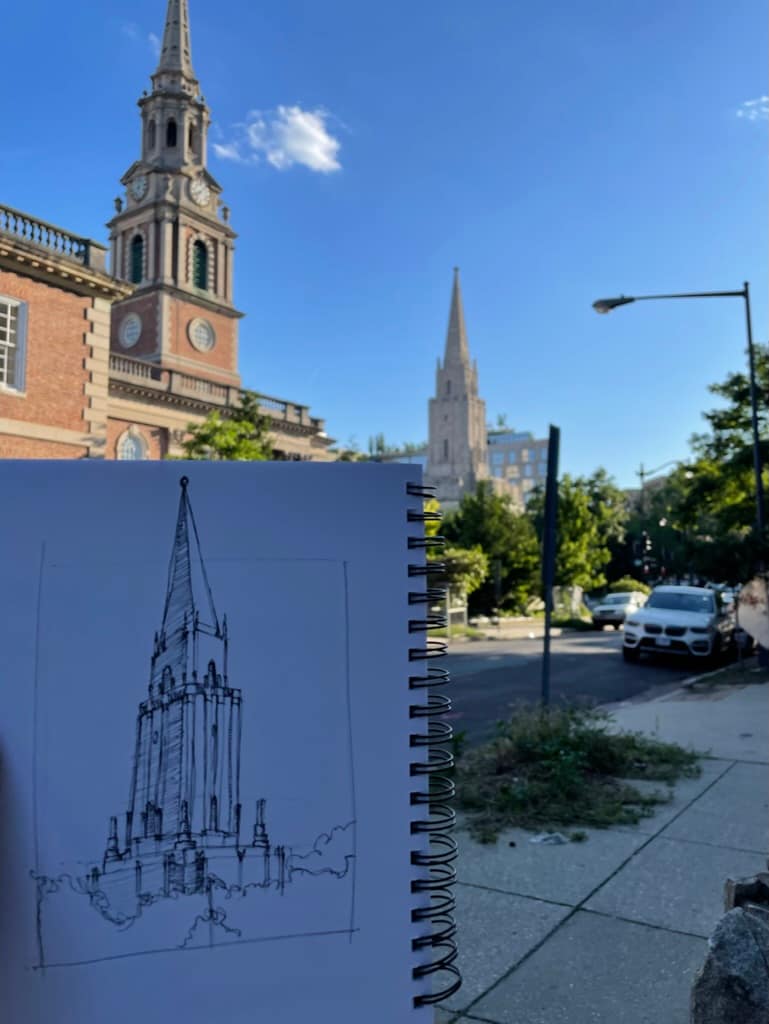

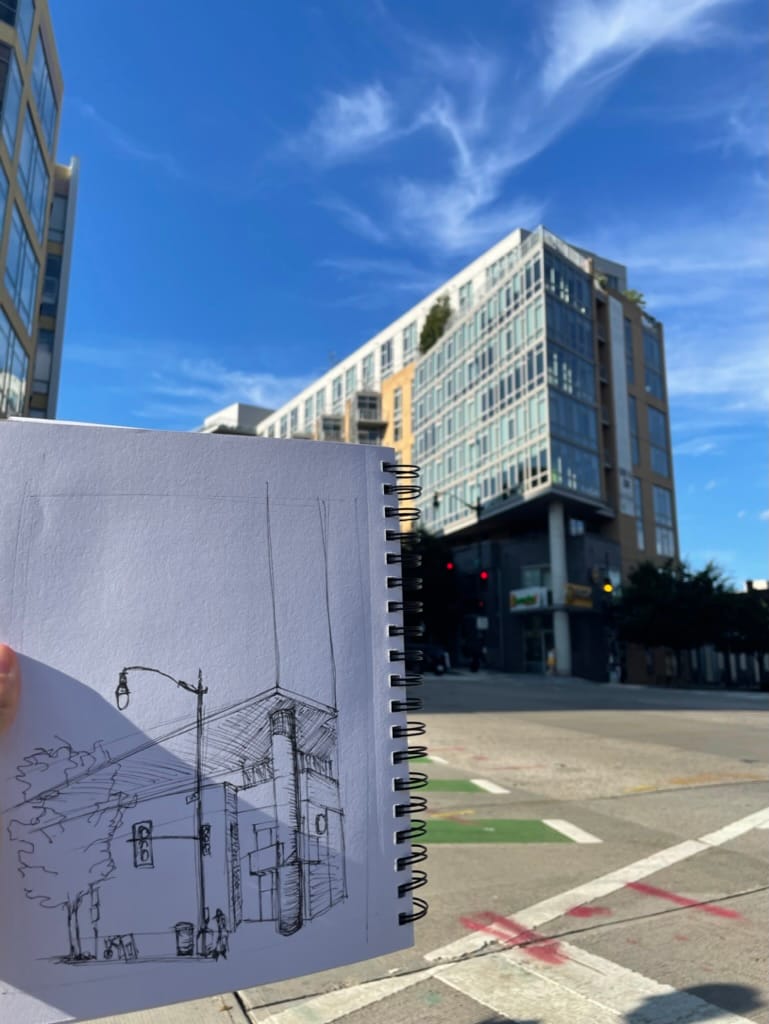

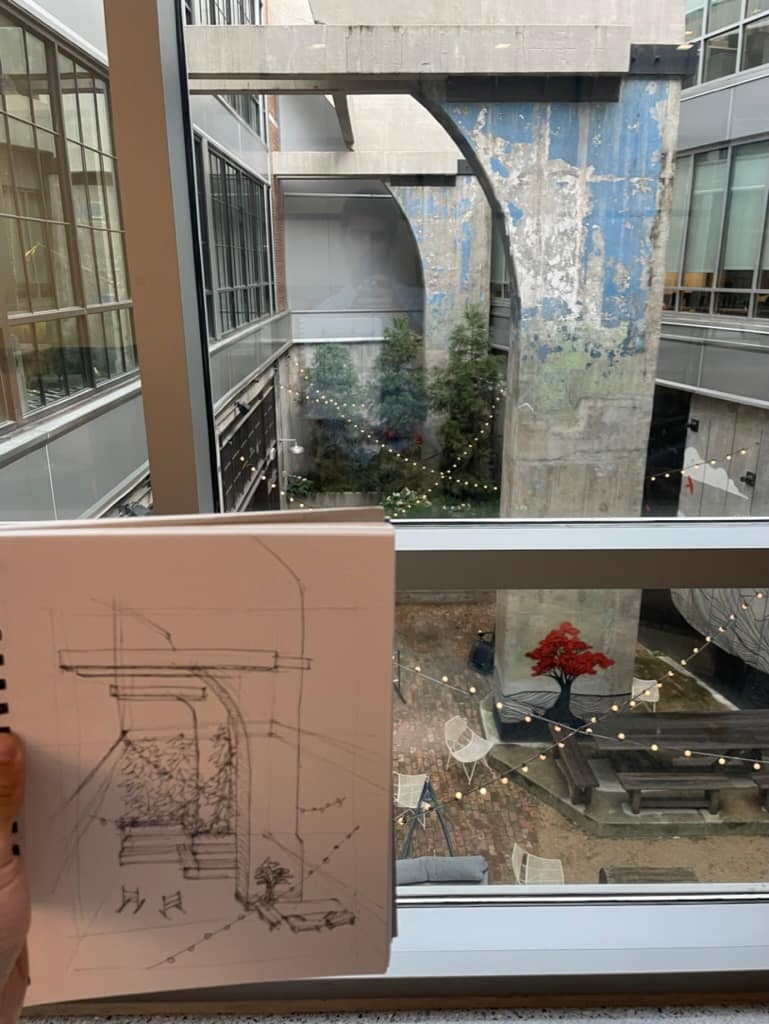

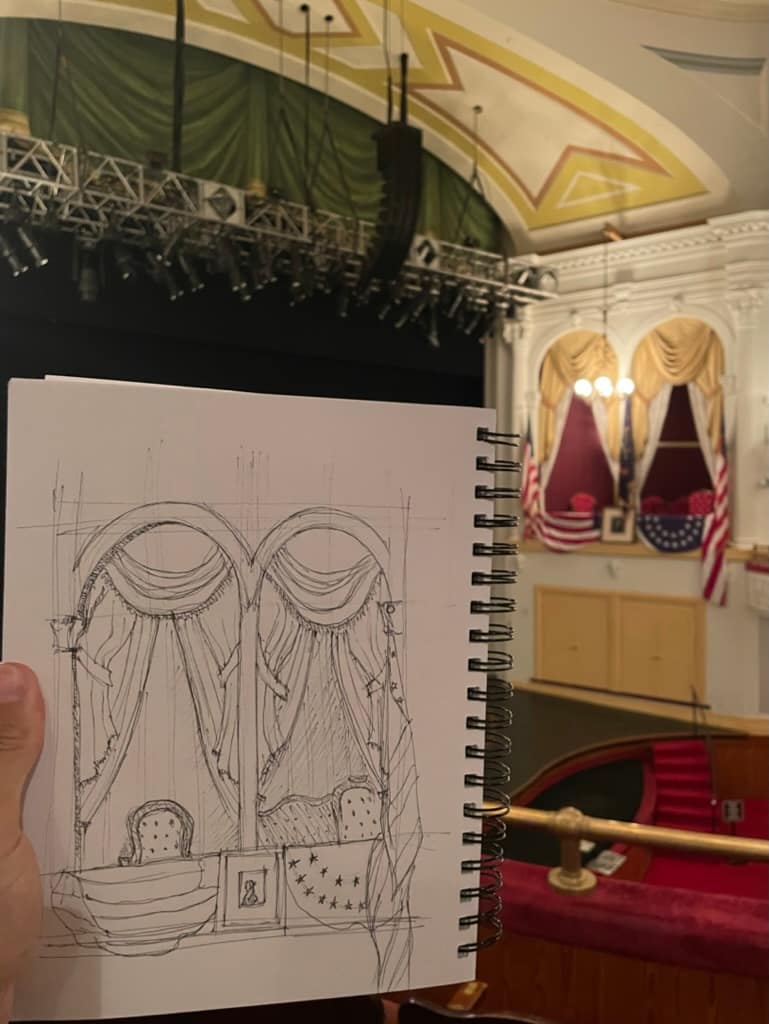

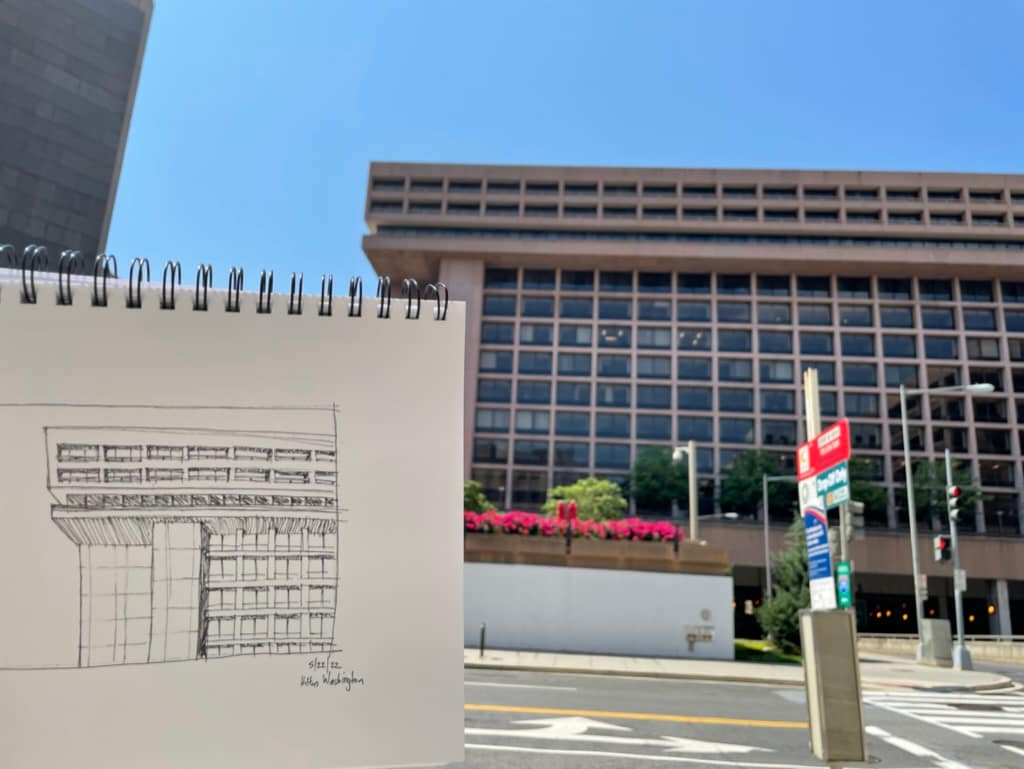

In 83 days, I completed 77 sketches. My first sketch was on May 22nd of the Hilton Washington next to L’Enfant Plaza and my last sketch was done on August 13th of the grand hall of Union Station. On average each sketch took me about 20 minutes. My usual routine consisted of me getting home from work between 5:30-6:00pm, changing out of work clothes and then walking around Columbia Heights to find something to sketch. On the weekends, I traveled to the museum/mall area, so content-wise they were different than my week-day sketches. On Wednesday I went salsa dancing, which left me very little time between getting home, eating and leaving, so I didn’t have time to sketch on those days and for the first few days when I had covid I couldn’t do anything. To make up for it, I sketched twice a day for a few days.

All of my sketches were done in a 7”x10” Canson XL mixed media paper sketch pad and 95% with a Staedtler .3/.2 pigment liner pen. 5% were done with a sharpie ultra fine pen, which is finer than a normal sharpie, but not as fine as the Staedtler. I used the sharpie for a few sketches because my .2 ran out of ink and I thought the .3 did too. I did not enjoy the sharpie. So much so, I tried the .3 again and it worked. It lasted me until my last sketch! It still had at least 50 sketches left in it. Sketching with a pen helps me be free, I stop thinking about making errors because errors can’t be erased and if you do, you just go over them darker. It creates layers to a sketch, which makes it more interesting. There is a visual representation of progress. For some reason, with a pencil, I can’t start. I don’t want to make mistakes, even though they can be erased.

In the beginning, I was sketching to copy. I was sketching what I saw. I don’t think this is necessarily a bad thing, but at the same time I did my last sketch with the sharpie ultra fine, I had been talking with my professor via email about sketching. In the image of the sketch I sent him, he commented about how it was crooked and I confirmed that it was crooked. I was standing holding the sketch pad and it’s hard to get things right. It wasn’t a sufficient excuse for him. What he didn’t see were construction lines. Construction lines are faint lines, “traces” of how you compose the sketch. Like someone who draws an oval before drawing a face. Construction lines help give a visual understanding of the relationship between certain forms (wall to window, arch to door, etc). After our conversation, I tried to be more conscious of what I was sketching and the relationship between the parts and the whole of what I was seeing. While being able to sketch isn’t a requirement for being an architect, it is a valuable skill to have. Through sketching, we better understand what is in front of us in a way that photography cannot.

Here are some of them: